Disclaimer: The Eqbal Ahmad Centre for Public Education (EACPE) encourages critical and independent thinking and believes in a free expression of one’s opinion. However, the views expressed in contributed articles are solely those of their respective authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the EACPE.

Introduction:

In the “intellectual indolence” that has reigned in Pakistan, Eqbal Ahmad has been a flare of exception. Although I became acquainted with his life and work long after his demise, his intellectual honesty, courage and brilliance has taught me to think, to learn and to question; inspiring me never to dim the dream of a progressive and peaceful Pakistan and world; to stay true to the pursuit of this vision. I am truly indebted to his work that has educated and awakened the importance of an intellectual consciousness in me. And I would like nothing more than to consider myself but a student of his.

Book Review:

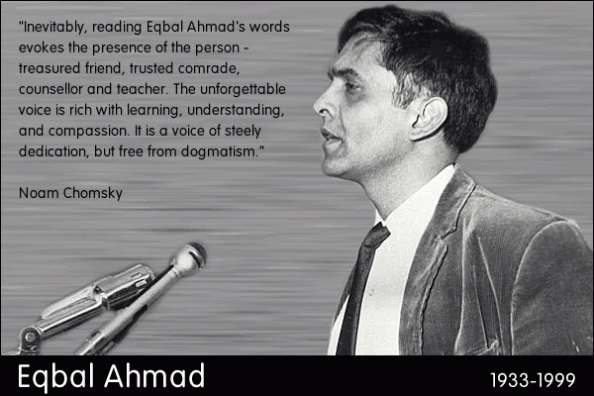

Political scientist, activist, writer, thinker and intellectual, Eqbal Ahmad (1930-1999) was a man beyond his times. Writing his obituary in 1999, the late Edward Said described him as a ‘Companion in arms to such diverse figures as Noam Chomsky, Howard Zinn, Tariq Ali, Ibrahim Abu-Lughod, Richard Falk’, and ‘perhaps the shrewdest and most original anti-imperialist analyst of Asia and Africa.’ Eqbal has rightly been called ‘the astute alarmist’ who uncannily foresaw future trends that later came to develop into concrete realities marking the world. And it is with six incredibly significant examples of this prophetic perspicacity, including the fallout of the Afghan War and that of a possible US invasion of Iraq, that Stuart Schaar begins his book on Eqbal Ahmad.

Professor Emeritus, Brooklyn College of the City University of New York, Schaar was friends with Eqbal since 1958 when they were both at Princeton. He carefully traces Ahmad’s journey from a little boy in Bihar who was an early witness to violence, a participant of the Partition, student at the Forman Christian College and Princeton University, one of the notorious Harrisburg 7 (a conspiracy case during the era of the Vietnam War in which the defendants were accused of a plot to kidnap Henry Kissinger), professor at Hampshire College in the US, to his return and final years in Pakistan. Each stage steering him towards the distinguished public intellectual and thinker he came to be; a transformation unveiled by light the book sheds on his personal, political and intellectual evolution.

Schaar writes, “The combination of originality, intelligence and fearlessness in confronting power, drew some of the major intellectuals on the Left towards him, including prominent figures in a variety of fields in the US, West

ern Europe, Africa, Latin America, and South Asia,. He socialized with writers from around the world and learned from them. He corresponded with leaders of the international Left and in the Indian/Pakistani subcontinent he knew and befriended some of the most gifted intellectuals, while political figures and military leaders courted him for advice.”

All in all, Schaar’s book weaves a truly vivid portrait of the man about whom the late Edward Said said, “Knowing him has been an education.”

Indeed Eqbal Ahmad’s brilliance and numerous travels led to his contact and correspondence with countless people, both those within and outside the realm of power, including Yasser Arafat, Ayatollah Khomeini, Frantz Fanon’s widow and Osama bin Laden, and various activists, diplomats, politicians, leaders, journalists, writers, revolutionaries from all over the world. The book makes sure to deal with this important aspect of his life. One of the instances, related to this, mentioned involves Habib Bourghiba’s attempts to get Ahmad to write his official biography while he stayed in Tunisia for his PhD thesis. Ahmad also came to be acquainted with various struggles, especially the liberation movement in Algeria against France.

As his friend, Schaar was able to gain insights not only from his own memories but also from the access he gained to the latter’s family, friends, colleagues and students. Their anecdotes and recollections paint a fuller picture of the person that Eqbal was in each of his relationships: as a father, teacher, friend, colleague and thinker.

One of these is dealt with in detail in the book: Eqbal’s friendship with Edward Said, a relationship of immense respect, admiration, solidarity and affinity between both. Regarding which the book holds some wonderful insights in the form of excerpts from the email correspondence between both and the letter of recommendation by Said when Ahmad applied for a job at Hampshire College.

Moreover, the book goes beyond illuminating Eqbal Ahmad’s words and ideas by engaging with his efforts and encounters through which he channelled his ideas and social and political activism; such as his role in organizing and establishing people-to-people Indo-Pak cultural exchanges back in 1980s, which Schaar writes, “[they] intended to build a social movement which would….help create a groundswell to move both countries towards reconciliation and peace.”, and his plan to establish a liberal-arts university in Islamabad by the name of Khaldunia (named after the Arab polymath).

Furthermore, Schaar manages to focus on both Eqbal Ahmad’s personal experiences and his ideas and work; by blending both as complements for each other into the narration of his life. To add clarity to the book and lend lucidity to understanding Eqbal’s work, the book neatly divides several of his ideas, stances and polemics on particular issues: (i) Islam and Islamic History; (ii) Imperialism, Nationalism, Revolutionary Warfare, Insurgency and Need for Democracy; (iii) The Middle East and the Palestinian-Israeli Conflict; (iv) India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh: the Problem of Nuclear Proliferation and Views on Partitioning States; and (v) Critique of US foreign policy: The Cold War and Terrorism. Although these sections do not cover the vast expanse of Eqbal’s ideas in detail, which perhaps can only be accessed through his essays, they are nonetheless, a fair glimpse of his perspective and analytical eminence.

Despite being his friend, Schaar does not remain from revealing Eqbal’s occasional idealism and resulting follies, such as his criticism and attacks on then prime-minister Benazir Bhutto and Asif Zardari in his Dawn columns all the while hoping and expecting her government to endorse and support his Khaldunia project, which consequently faced many hurdles to its realization.

However, Kabir Babar sees the book as not without its drawbacks for students of Eqbal new and old:

“This book is not without its flaws. A drawback of the anecdotal style in which it is written is that Ahmad’s life is presented with neither chronological nor thematic consistency.

And while the book is revealing, it is by no means a definitive biography, for there are numerous aspects of Eqbal Ahmad’s life that are either ignored or glossed over in this work. For instance, no mention is made of Ahmad’s encounters with Malcolm X and Fidel Castro. Also, while much is made of the impact that Ahmad’s exposure as a boy to Mohandas K. Gandhi and Rabindranath Tagore had on his thought, there is no reference to Syed Abul Ala Maududi, to whom Eqbal acknowledged owing an intellectual debt. Ahmad is said to have directly participated in the Algerian revolution, but few details are provided. In his foreword to a collection of Ahmad’s essays, physicist Pervez Hoodbhoy states that, during successive martial law governments in Pakistan, there were warrants of arrest and death sentences put out on Ahmad. None of this is mentioned in Schaar’s book.”

And while the book is revealing, it is by no means a definitive biography, for there are numerous aspects of Eqbal Ahmad’s life that are either ignored or glossed over in this work. For instance, no mention is made of Ahmad’s encounters with Malcolm X and Fidel Castro. Also, while much is made of the impact that Ahmad’s exposure as a boy to Mohandas K. Gandhi and Rabindranath Tagore had on his thought, there is no reference to Syed Abul Ala Maududi, to whom Eqbal acknowledged owing an intellectual debt. Ahmad is said to have directly participated in the Algerian revolution, but few details are provided. In his foreword to a collection of Ahmad’s essays, physicist Pervez Hoodbhoy states that, during successive martial law governments in Pakistan, there were warrants of arrest and death sentences put out on Ahmad. None of this is mentioned in Schaar’s book.”

Nonetheless, Babar is right to point out that, “The subtitle of this book is well-chosen: because he was ideologically difficult to pigeonhole and the scope of his activities and intellect was global, Eqbal Ahmad was an outsider everywhere.”

All in all, Schaar’s book weaves a truly vivid portrait of the man about whom the late Edward Said said, “Knowing him has been an education”, and on occasion of his [Ahmad] retirement from Hampshire College, “..to paraphrase from Kipling’s Kim – a friend of the world.” Eqbal was a friend who saw the future before its time, who was an ally of the oppressed and dispossessed all over the world and was an epitome of intellectual honesty and courage – a friend who, in today’s global moment of confusion, crises and clamour, is all the more important to revisit. A revisit for which Schaar builds an important bridge through this book, for there is no doubt that knowing Eqbal Ahmad even today would still be an invaluable education for anyone seeking guidance and direction in hope for a more just, progressive and peaceful world.

References:

[3]- The pictures used in the review (second) was previously available on eBay by Historic Images Inc, located in Memphis, TN. The book is available for order from Oxford University Press Pakistan and all good bookshops. Find out more details at this link.

Contributed by Hafsa Khawaja

An undergraduate student writing on socio-political affairs. She blogs here.

And while the book is revealing, it is by no means a definitive biography, for there are numerous aspects of Eqbal Ahmad’s life that are either ignored or glossed over in this work. For instance, no mention is made of Ahmad’s encounters with Malcolm X and Fidel Castro. Also, while much is made of the impact that Ahmad’s exposure as a boy to Mohandas K. Gandhi and Rabindranath Tagore had on his thought, there is no reference to Syed Abul Ala Maududi, to whom Eqbal acknowledged owing an intellectual debt. Ahmad is said to have directly participated in the Algerian revolution, but few details are provided. In his foreword to a collection of Ahmad’s essays, physicist Pervez Hoodbhoy states that, during successive martial law governments in Pakistan, there were warrants of arrest and death sentences put out on Ahmad. None of this is mentioned in Schaar’s book.”

And while the book is revealing, it is by no means a definitive biography, for there are numerous aspects of Eqbal Ahmad’s life that are either ignored or glossed over in this work. For instance, no mention is made of Ahmad’s encounters with Malcolm X and Fidel Castro. Also, while much is made of the impact that Ahmad’s exposure as a boy to Mohandas K. Gandhi and Rabindranath Tagore had on his thought, there is no reference to Syed Abul Ala Maududi, to whom Eqbal acknowledged owing an intellectual debt. Ahmad is said to have directly participated in the Algerian revolution, but few details are provided. In his foreword to a collection of Ahmad’s essays, physicist Pervez Hoodbhoy states that, during successive martial law governments in Pakistan, there were warrants of arrest and death sentences put out on Ahmad. None of this is mentioned in Schaar’s book.”