In much of the world, universities thrum with the energy of social change. A physical environment that fosters learning and exploration is why meticulous attention is paid to aesthetics together with, of course, high academic goals. Imagine sprawling green spaces, visually pleasing architecture, and a pervasive sense of freedom to think. Laughter and lively discussions fill the air as students, attired in a kaleidoscope of colours and dresses, mingle, relax, or delve into their studies.

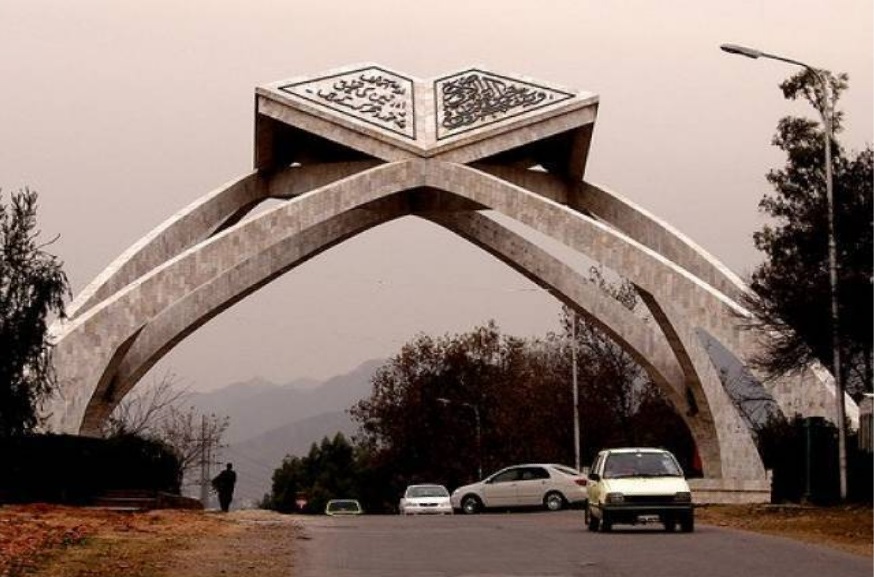

As a freshly appointed lecturer, I remember an American physics professor who visited Quaid-e-Azam University (QAU) back in 1973-1974. He was awestruck by the beauty of his surroundings remarking that, with Cornell University excepted, it surpassed all he’d seen back home. There was lush greenery everywhere, from behind the hills flowed a stream of sparkling clear water, native colourful flowers bloomed, and modest but dignified-looking buildings functioned as departments of various natural and social sciences.

Fifty years ago, QAU was new but it looked like a university, felt like a university, and had a living campus. Male and female students, separately and together, frequented impromptu cafes (khokhas) to enjoy tea and snacks. Academic standards were not high except in two departments — physics and economics — but things looked generally good and optimism was in the air.

What if that American professor were to visit QAU today? Would he think he has landed in some open-air prison? Or a military cantonment? He would see 10-foot-high walls topped with razor wire everywhere, literally miles and miles of them, mostly built in the last two to three years. Where laughter and gaiety once were, there is now the grim solemnness of beards and burqas. Individuality is just a weed, ruthlessly yanked from the fertile ground of self-expression. There are no music concerts, no artistic or aesthetic creations.

A groundless obsession with security has transformed even the physical appearance of this university.

No one I spoke to could explain what occasioned these recent massive fortifications. It seems that every bit of money that the university charges from its students or receives from the government has been spent on this. Apparently, none remains to fix broken and stinking toilets, crumbling concrete, and manifest decay of the physical infrastructure. It is said that a few powerful professors and contractors conspired — all of them filling their pockets with the construction money. Who knows?

Madness has taken over. For decades, my department was a pleasant, seven to eight-minute daily walk from my former home on campus. But walls, barbed wires, gates and check-posts everywhere have made that same journey impossible. To go from point A to point B on campus is not easy anymore. Student hostels have been doubly fortified.

Why such extreme protective measures? Are these preparations for some war? Is QAU anticipating that Changez Khan will invade again from Mongolia? Or that TTP is planning another APS-style attack?

Terrorism was at a high level in Pakistan between 2002 and 2016. Suicide bombings targeted shopping malls, markets, and mosques in Islamabad but the university campus remained totally safe. While ethnic and religious student groups have clashed violently, there hasn’t been a single incident of terrorism on campus.

Glaringly, the new walls are not for protecting QAU’s land from further encroachments. Of the original 1,709 acres given to the university by the government in the mid-1960s, roughly 300-400 acres have been stolen. Old land records have been tampered with and patwaris have been suitably bribed to change lathas.

In January 2019, bulldozers were dispatched at then prime minister Imran Khan’s orders to demolish the house of a powerful politician who had seized the university’s land and built his mansion. They razed its boundary walls but some insider PTI-PPP deal led to their retreat two hours later. Last week, I drove past a board with ‘X’s residence’ freshly painted on it. Placed provocatively by the roadside, it is meant to be a slap in the face of all those who have fought to save the university’s land.

While the obsession with securitisation has reached absurd limits at QAU, the bunker mentality is practically everywhere. Gated communities in cities, for example, are now ubiquitous as living spaces. Whether the intent is to create a moat around inequality, or perhaps for ethnic or sectarian reasons, low levels of social trust are manifest in a sense of besiegement. In Pakistan’s first few decades you could go anywhere from one part of a city to another, military cantonments excepted, without encountering any checkpoints. That is no longer possible.

A fortress mentality is also visible — albeit to a lesser extent — in other universities across the country. Their physical environments have become less and less open. On many campuses, CCTV cameras track students, ostensibly for security reasons. The hidden agenda, however, is to regulate personal behaviour.

At the core lies a fundamental question: what is university education designed to achieve? There are two widely different approaches.

The first is that of the modern world. Except for those at the very bottom of the heap, universities from Europe to America and in China or India, seek to sharpen mental faculties across disciplines and create a mindset suited for an ever-changing world. Cultivation of critical faculties for evaluating facts, and making independent judgements, is the desired outcome.

The second aim at breeding a dutiful student who is passive, obedient, defers readily to authority, and will duly memorise and reproduce whatever his professor teaches. In Pakistan’s cultural and religious environment, individualism is dangerous and undesirable. An authoritarian and moralising attitude, with the imposition of dress codes, seeks to limit personal freedoms to the barest minimum. Expressions of joy, such as celebrating Basant, are curtailed. Hence a tightly regulated, dour and walled-in physical environment works better than colourful openness.

The pathological securitisation of Pakistan’s university campuses and their grimness underscores a deep disconnect. The kind of education sought by a free, open, and modern society differs fundamentally from the notion of education held in a militaristic, autocratic and feudal set-up (replete with its private jails). Evolving cultural and religious norms could change things for the better but the process is slow and not guaranteed.