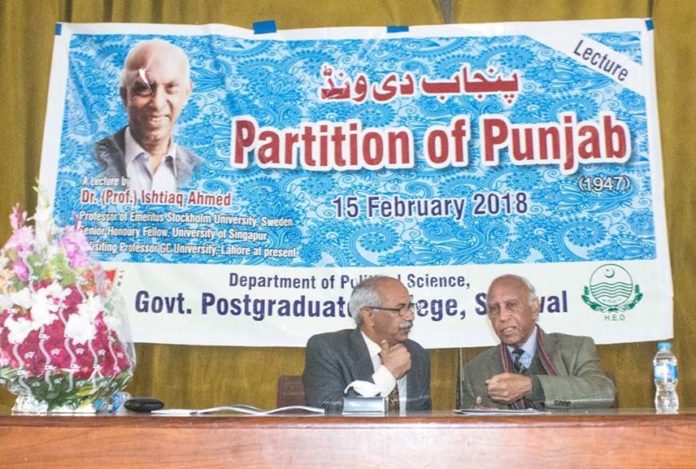

On 15 February 2018 I had the privilege of visiting Sahiwal on the invitation of the Principal of Government College Sahiwal (established in 1946 as Government College Montgomery) Prof Dr Akhlaq Hussain. My friend Shafiq Butt of Punjab Lok Sujag and Zakria Khan facilitated the visit as they arranged for my first visit to Sahiwal in 2015. The topic now and then was the partition of the Punjab in 1947.

Known before the partition as Montgomery, it was one of the three modern towns the British had built along with its vast canal and barrage systems which had converted the semi-desert western Punjab into the granary of India. The other two towns were Lyallpur (Faisalabad) and Sargodha. Once upon a time, Hindus and Sikhs along with Muslims were settled in large numbers in the canal colonies from other parts of the undivided Punjab.

The most important historical event from Sahiwal and its adjoining areas was the heroic struggle of Rai Ahmed Khan Kharal, an 80-year old chieftain of that region who resisted the British annexation of that part of the Punjab. The Kharals, Wattoos and several other tribes of that region are known by a name I find offensive — Janglee (the wild people). They constituted a pastoral community which the British canal system displaced with settled agriculture. As a result, a prolonged guerrilla war took place in 1857. Ahmed Khan Kharal was captured, executed and beheaded. In revenge his followers captured Assistant Commissioner Mr Berkley (later Lord Berkley) and killed him. The hero of one is the villain of the other — I suppose this is the fairest way of interpreting and understanding history.

But let me return to the lecture at Government College Sahiwal. It was very well attended and both faculty and students were present in large numbers. Prof Goraya, the chairman of the Political Science Department sat with me on the dais and I had more than an hour to present my three stages in the partition of the Punjab: stage one from early March 1947 which lasted two weeks in which Lahore, Amritsar, Multan and Rawalpindi went through communal rioting.

Naseeb Kaur told me that in 1991 someone knocked at her door: and lo and behold; an old, wrinkled but familiar face looked at her after 45 years. Mother and daughter were reunited at last. The mother was a pious Muslim woman who prayed five times a day and the daughter an orthodox, devout Sikh.

Stage two, when Lord Mountbatten took up charge as Viceroy on 24 March and till power was handed over to the two Punjabs created by the Radcliffe Line. Stage three, extending from August 15 to December 31, 1947 in which the two administrations were complicit in getting rid of unwanted minorities: 6 million Muslims from the Indian East Punjab and 5.4 million Hindus and Sikhs from the Pakistani West Punjab.

And now to the idea of Justice, I narrated some real-life stories I had collected during my research. One of them was about a four-year old Muslim girl who in October 1947 was separated from her mother in Ropur district of eastern Punjab. Thousands of Muslims, mostly Gujjars, were killed during that raid but many survived and reached Pakistan. However, that little girl was left standing among dead bodies when a Sikh woman took her and brought her to a Sikh who had taken part in that raid. Now, when he saw this tiny helpless girl — his sense of sympathy and humanity was aroused. He adopted her as his own daughter. Later, when she grew up she was married. When I met her in early January 2005 she was a grandmother with children and grandchildren. She had been named Naseeb Kaur by her Sikh adoptive father. He had done very well in business after he had adopted her and even had two sons born to him after many years of waiting for a child.

Her mother who had gone to Pakistan would visit Nankana Sahib every year when Sikh pilgrims visited the holy site and enquire about anyone who might have come from those villages of Ropar. Finally one day, she met the woman who had saved her daughter and given her to the Sikh who adopted her as his own child. She pleaded with the Indian High Commission in Islamabad for a visa and someone took pity on her and granted her the visa.

Naseeb Kaur told me that in 1991 someone knocked at her door: and lo and behold an old, wrinkled but familiar face looked at her after 45 years. Mother and daughter were reunited at last. The mother was a pious Muslim woman who prayed five times a day and the daughter an orthodox, devout Sikh. That is when Naseeb Kaur learnt that her Muslim name was Azmat Bibi.

Naseeb Kaur told me that she was very much at peace with her Sikh faith and that had created no problems because mother and daughter and their families in the Indian East Punjab and the Pakistani West Punjab had accepted the reality of two faiths sincerely and warm-heartedly.

Prof Aurangzeb, himself a political scientist but now retired, asked me, “Would Naseeb Kaur, who became a Sikh by an accident of fate in 1947 be entitled to go to Heaven?”

I don’t know what the theologians would give as the answer, but this is what I said:

“We as academics and teachers know that we must give marks to our students based strictly on their performance. Merit and merit alone should guide our marking and not anything else. Sir Ganga Ram, a Hindu did more for the people of Punjab by building hospitals, schools, roads, colleges, canals, roads and much more. I think he deserves to go to Paradise much more than me, a sinner without any great social work to his credit. If he cannot be admitted to Paradise because he was a Hindu,then I prefer to be in Hell because to me that is true justice.”

The spontaneous clapping which followed was simply astounding. I came back convinced that people in general can make sound and fair judgments. Hats off to the students and faculty of Government College Sahiwal. I hope one day my Idea of Justice becomes the basis for dealing with one another in this world without any prejudice. What happens after death can remain a mystery.

About the Author:

Dr. Ishtiaq Ahmed is Professor Emeritus of Political Science, Stockholm University; Visiting Professor Government College University and Honorary Senior Fellow, Institute of South Asian Studies, National University of Singapore. He can be reached at billumian@gmail.com