Disclaimer: The Eqbal Ahmad Centre for Public Education (EACPE) encourages critical and independent thinking and believes in a free expression of one’s opinion. However, the views expressed in contributed articles are solely those of their respective authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the EACPE.

Right-wing populism has gained new prominence in the arena of politics since the rise of Donald Trump in the US, and likewise manifested in the rise of PTI in Pakistan. The major theme of populism is its appeal to emotions rather than reason and its anchoring pillars are rhetoric against democracy and public representation in politics. Otherization of opponents becomes a signature of its political praxism.

While its vivid target is invariably the status quo and its players, the major aim is always the democratic transition and institutionalized parliamentary form of politics. Populism usually begins when a system of power is riddled with various forms of contradictions, like the rise of middle class in a newly modernized economy, or emergence of neo-middle class owing to knowledge economy and network society. As the power system remains, by and large, static, populism takes place in the hearts and minds of middle class bringing them on the far right spectrum of politics as it has happened in Pakistan since last decade. Secondly, the lack of coordination amongst traditional political parties usually provide ample vacuum in the domain of cyberspace and social setup that populistic rhetoric gains supremacy over legal and constitutional framework of nation-state.

Whenever old or new political actor fails to impose its political hegemony over people, it tends to invoke subconsciousness of masses against the current political system to subjective musings. As democratic transition and the movement of rule of law in Pakistan gained prominence in the aftermath of Lawyers’ Movement of 2007, the traditional ruling elite asserted its influence and power over discourse and policy through populistic discourse to discredit all the democratic forces of Pakistan.

Up until recently, there was little challenge to the hegemony of the right-wing in Pakistan. For the past few decades, right-wing groups and state elites have remained closed allies and built on each other’s strengths. However, two major political changes in the recent past have put the survival of this hegemonic alliance at risk.

First, the post 9/11 scenario has created a major rupture in state discourse and policy that makes it increasingly difficult for state elites to maintain their open association with militant rightists. Therefore, it has been necessary to reinvent the old right-wing into a more palatable populism. Secondly, the hegemony of the so called holy alliance has been challenged by a vibrant and assertive parliament in the aftermath of the 2008 general election.

Not only has the present parliament restored constitutional democracy, it also ousted Musharraf, reinstated the judiciary, put the peace dialogue with India back on track and formulated a consensus based policy against terrorism. These are no small achievements given the divided mandate and diverse representation in the elected houses.

Although the ideas of the people and fundamental rights occupy central positions in democracy, they can be just as easily emptied of their substantive meanings. In post-modernist terms, these concepts are floating signifiers without specific referents. They can be invested with diverse and indeterminate meanings.

Both populism and constitutional democracy have contrasting approaches towards the question: what constitutes the people? Populism conceptualises the people as a homogeneous/monistic body invested with popular sovereignty. Therefore, populists demand direct and unmediated power to the people.

On the other hand, the logic of representative democracy presumes plural interests and factional divisions in society. Hence, it emphasises participation, representation and democratic accommodation.

Several scholars of political studies are of the view that populism has potentially dangerous consequences for democracy. In democratic regimes, both the identity and the will of the people are subject to constant reinterpretation.

Temporary and mediated construction is necessary given the diverse and ever-changing needs, interests and beliefs of citizens. Parliament assumes great significance in this regard because it allows the expression of difference as well as the construction of political unity through diversity.

On the contrary, populism defines the sovereign rule of the people-as-one. Consequently, it divides society into two extremely antagonistic and homogenous groups, namely ‘the pure people’ versus ‘the corrupt elites’.

The success of new-right populists lies in their alliance with the proponents of judicial activism and sections of the media that have a self-anointed agenda-setting role.

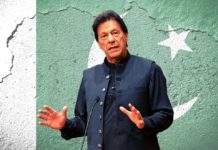

Populists contend that ‘the people’ are the real sovereign but corrupt and incompetent political representatives have stolen power from them. They claim to embody the will of ‘the people’ and vow to give power back to ‘the people’. Populism has become the pet strategy of new rightists in Pakistan, mainly because of its thin-centred ideology as well as its potential to cultivate disenchantment with politics and the new democratic order. Not surprisingly, new-right populist leaders like Imran Khan allege that parliament is merely a rubber-stamp in the hands of corrupt and self-interested politicians. They claim to have simple solutions to all of Pakistan’s complex and historical problems.

The success of new-right populists lies in their alliance with the proponents of judicial activism and sections of the media that have a self-anointed agenda-setting role.

Discussing the alliance of right populists and judicial activists against representative democracy in Canada, Rainer Knopff, the renowned scholar of political science, observes that while populism seeks to move power down, from representatives to the people, the politics of fundamental rights moves power up, away from elected parliamentarians to appointed judges.

Similarly, the media, particularly current affairs anchors, regularly deploy news frames which indict political leaders for poor governance and disregard for national interests.

Politics is portrayed as a dirty game of power-hungry politicians, a narrative that gives rise to cynical and anti-politics attitudes within the general public. In many instances, the media openly espouses populism and directly makes political appeals to ‘the people’.

There are, however, certain limits to new-right populism in Pakistan. Unlike typical populists, this new brand declares war against the corruption and bad governance of the political class while conveniently excusing state and economic elites. Moreover, they are faced with the challenge of an alternative populist construction of the people as historical and linguistic communities. The condition of ethno-linguistic diversity and rise of nationalist movements in Pakistan make the singular and unifying conception of the people almost an impossible task.

A contributed article by Hammad Raza