Pakistan’s mad rush towards the cliff edge and its evident proclivity for collective suicide deserves a diagnosis, followed by therapy. Contrary to what some may want to believe, this pathological condition is not one man’s fault and it didn’t develop suddenly. To help comprehend this, for a moment imagine the state as a vehicle with passengers. It is equipped with a steering mechanism, outer body, wheels, engine and fuel tank.

Politics is the steering mechanism. Whoever sits behind the wheel can choose the destination, speed up, or slow down. Choosing a driver from among the occupants requires civility, particularly when traveling along a dangerous ravine’s edge. If the language turns foul, and respect is replaced with anger and venom, animal emotions take over.

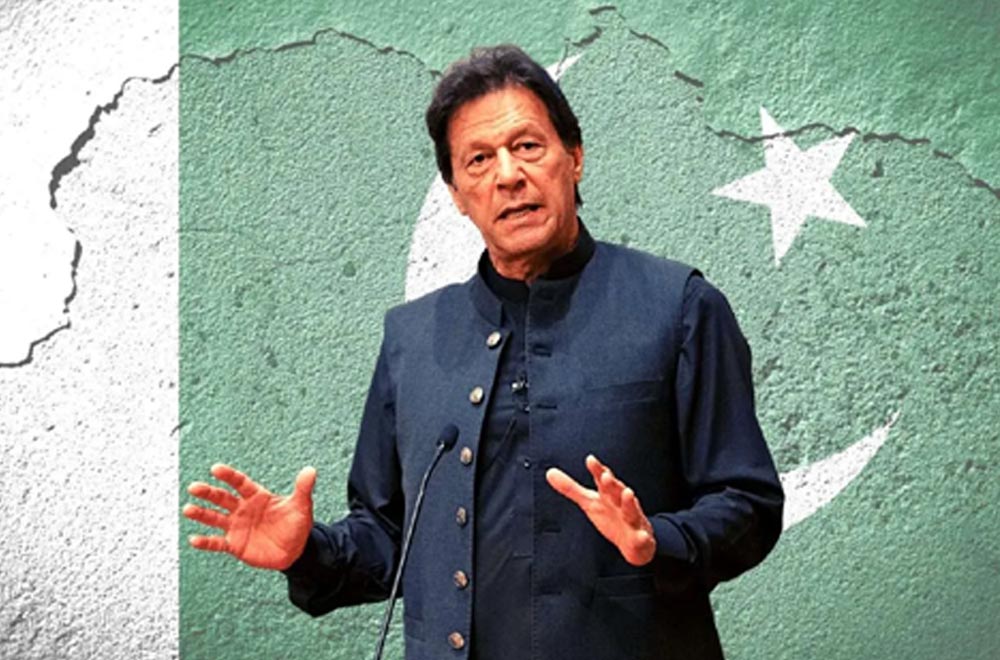

Imran Khan started the rot in 2014 when, perched atop his container, he hurled loaded abuse upon his political opponents. Following the Panama exposé of 2016, he accused them — quite plausibly in my opinion — of using their official positions for self-enrichment. How else could they explain their immense wealth? For years, he has had no names for them except chor and daku.

But the shoe is now on the other foot and Khan’s enemies have turned out no less vindictive, abusive and unprincipled. They have recorded and made public his recent intimate conversations with a young female, dragged in the matter of his out-of-wedlock daughter, and exposed the shenanigans of his close supporters.

More seriously, they have presented plausible evidence that Mr Clean swindled billions in the Al Qadir and Toshakhana cases. Which is blacker: the pot or the kettle? Take your pick.

Pakistan’s downward spiral owes to misplaced priorities, the army’s role, and deliberate miseducation.

Everyone knows politics is dirty business everywhere. Just look at the antics of Silvio Berlusconi, Italy’s corrupt former prime minister. But if a vehicle’s occupants include calm, trustworthy adjudicators, the worst is still avoidable. Sadly Pakistan is not so blessed; its higher judiciary has split along partisan lines.

The outer body is the army, made for shielding occupants from what lies outside. But it has repeatedly intruded into the vehicle’s interior, seeking to pick the driver. Free-and-fair elections are not acceptable. Last November, months after the Army-Khan romance soured, outgoing army chief General Qamar Javed Bajwa confessed that for seven decades the army had “unconstitutionally interfered in politics”.

But a simple mea culpa isn’t enough. Running the economy or making DHAs is also not the army’s job. Officers are not trained for running airlines, sugar mills, fertiliser factories, or insurance and advertising companies. Special exemptions and loopholes have legalised tax evasion and put civilian competitors at a disadvantage.

A decisive role in national politics, whether covert or overt, was sought for personal enrichment of individuals. It had nothing to do with national security.

While Khan has focused solely on the army’s efforts to dislodge him, his violent supporters supplement these accusations by disputing its unearned privileges. When they stormed the GHQ in Rawalpindi, attacked an ISI facility in Pindi, and set ablaze the corps commander’s house in Lahore, they did the unimaginable. But, piquing everyone’s curiosity, no tanks confronted the enraged mobs. No self-defence was visible on social media videos. The bemused Baloch ask, ‘What if an army facility had been attacked in Quetta or Gwadar?’ Would there be carpet bombing? Artillery barrages?

The wheels that keep any economy going are business and trade. Pakistanis are generally very good at this. Their keen sense for profits leads them to excel in real-estate development, mining, retailing, hoteliering, and franchising fast-food chains. But this cleverness carries over to evading taxes, and so Pakistan has the lowest tax-to-GDP ratio among South Asian countries.

The law appears powerless to change this. When a trader routinely falsifies his income tax return, all guilt is quickly expiated by donating a dollop of cash to a madressah, mosque, or hospital. In February, the pious men of Markazi Tanzeem Tajiran (Central Organisation of Traders) threatened a countrywide protest movement to forestall any attempt to collect taxes. The government backed off.

The engine, of course, is what makes the wheels of an economy turn. Developing countries use available technologies for import substitution and for producing some exportables. A strong engine can climb mountains, pull through natural disasters such as the 2022 monster flood, or survive Covid-19 and events like the Ukraine war. A weak one relies on friends in the neighbourhood — China, Saudi Arabia, and UAE — to push it up the hill. By dialling three letters — I/M/F — it can summon a tow-truck company.

The weakness of the Pakistani engine is normally explained away by various excuses — inadequate infrastructure, insufficient investment, state-heavy enterprises, excessive bureaucracy, fiscal mismanagement, or whatever. But if truth be told, the poverty of our human resources is what really matters.

For proof, look at China in the 1980s, which had more problems than Pakistan but which had an educated, hard-working citizenry. Economists say that these qualities, especially within the Chinese diaspora of the 1990s, fuelled the Chinese miracle.

The fuel, finally, is the human brain. When appropriately educated and trained, it is voraciously consumed by every economic engine. Pakistan is at its very weakest here. Small resource allocation for education is just a tenth of the problem.

More importantly, draconian social control through schools and an ideology-centred curriculum cripples young minds at the very outset, crushing independent thought and reasoning abilities. Leaders of both PTI and PDM agree that this must never change. Hence Pakistani children have — and will continue to have — inferior skills and poorer learning attitudes compared to kids in China, Korea, or even India.

The prognosis: it is hard to see much good coming out of a screeching catfight between rapacious rivals thirsting for power and revenge. None have a positive agenda for the country.

While the much-feared second breakup of Pakistan is not going to happen, the downward descent will accelerate as the poor starve, cities become increasingly unlivable, and the rich flee westwards. Whether or not elections happen in October and Khan rises from the ashes doesn’t matter. To fix what has gone wrong over 75 years is what’s important.