The university is like a mini-corporate-government, where there has been a huge amount of training in how not to deal with relevant issues. But a good education should make manifest the organic, living links between abstract principles and individual and group behavior. So when you talk of democracy, you practice it. When you talk of freedom, you live it. Because the function of good intellectual work is to apprehend reality, in order to change it.

– Eqbal Ahmad, “Revolution in the Third World”

In an interview with David Barsamian, the renowned leftist broadcaster of Alternative Radio, Eqbal reflected on the years that would come to define him, from his early life through to the 1960s. Growing up in Bihar during the tumultuous Partition of India and Pakistan, Eqbal witnessed firsthand what he described as “the ease with which perfectly good humanity can descend into barbarism,” a decline profoundly driven by ideological forces. The experience would later inform his critical views on nationalism.In the late 1950s, Eqbal journeyed to the United States for his academic pursuits, undertaking a Masters in American Studies at Occidental College before pursuing a doctorate in Political Science at Princeton University, where he wrote a dissertation on Tunisian labor movements. His fieldwork took him to North Africa, where he became captivated by the Algerian revolution, an experience further enriched by his meeting with Frantz Fanon. Both left lasting impressions on him.

Notably, what stands out in Eqbal’s discussion with Barsamian is his thoughts on intellectuals. Eqbal cites two pivotal realizations that cemented his staunch anti-imperialism. The first was the impact of Cold War anticommunism on American intellectual and moral life. Though Eqbal held great respect for his professors at Princeton, he was struck by how many served as consultants for the CIA, the Department of Defense, or the State Department. He remarked:

There was no discredit or stigma attached to the idea of intellectuals becoming functionaries. There was no inhibition about organic or any kind of deep linkages between power and knowledge. In a sense, I had never seen that before. Nationalist politics in India, which I had experienced in India and Pakistan, was one of opposition to the colonial state. And the post-colonial politics that I witnessed in Pakistan included such things as a major figure like Faiz Ahmed Faiz going to prison. To me, the relationship between intellectuals and power, between knowledge and power, was by definition adversarial. I found this to be completely merged and integrated in the U.S.

While he observed this integration of knowledge and power within the American academy, Eqbal found the adversarial spirit he valued within the civil rights and burgeoning antiwar movement. He came to appreciate and admire these movements for what he described as “the goodness that dissent had introduced into American social and cultural life.” They provided powerful examples of how collective action could challenge American power and counter the conformity he found in academia. He became more convinced of the essential role of intellectuals as challengers to power, rather than mere functionaries within it.

In 1967, Noam Chomsky encapsulated this political ethos in the New York Review of Books with his article “The Responsibility of Intellectuals.” Quite amusingly, I learned that this piece was first delivered as a public talk to the Harvard Hillel Society and later published in their student journal, Mosaic. Reflecting on the article at a 2017 conference to celebrate it, Chomsky remarked, “This was pre-1967, and things were different.” Notwithstanding its original intended audience, the article would go on to become a foundational critique of the Cold War’s influence on American cultural and intellectual life.

During a period of escalating US militarism in Vietnam, Chomsky sought to challenge and reorient intellectuals who had been complicit in supporting imperialism. In this charged climate, Chomsky urged intellectuals to take a stand against the war and the misinformation propagated by the state and media. He criticized those who passively accepted, rationalized, or actively supported US military actions through their silence or complicity. By emphasizing three key responsibilities of intellectuals — speaking truth and exposing lies, providing historical context, and unveiling the role of ideology — Chomsky challenged the limits Cold War consensus imposed on public debate.

Eqbal stood alongside Chomsky, publicly challenging the exceptional nature of US imperial power. In his renowned 1965 essay “Revolutionary Warfare: How to Tell When the Rebels Have Won,” published in The Nation magazine, Eqbal embodied the intellectual responsibilities Chomsky later articulated, as he sought to dispel misconceptions about revolutionary warfare and correct American views on the Vietnam War. The essay aimed to challenge Washington’s conspiratorial belief that the Vietnamese insurgency thrived mainly due to external agitators, active sanctuaries, political irreverence, and the use of terrorism.

Eqbal, a dedicated student of revolutionary warfare and a witness to the Algerian revolution, offered insightful interpretations of global revolutionary movements. He highlighted Mao’s success in China and the setbacks experienced by the US in Cuba, Korea, and Laos to argue that America’s strategy had been largely defensive, focusing on containing the spread of revolutionary movements. However, he cautioned that “wrong premises do not usually produce right policies,” warning that failing to grasp the political factors driving popular support in Vietnam could lead to ongoing failure and increased loss of life. Eqbal pointed out that the Vietnamese insurgency aimed not just to outfight the enemy but also to out-administer them, emphasizing the significance of understanding the political elements that facilitated mass mobilization and contributed to their success.

“Eqbal also issued a stark warning: without the fear of sanctions, a foreign power in counter-guerrilla struggles may resort to genocide as a final move for ‘victory.’”

Eqbal alerted the American public to the destruction being wrought in Vietnam in their name, arguing further that Americans could find genuine solidarity with the Vietnamese people, who were fighting for freedom much like they were. Indeed, drawing parallels with the French defeat in Indochina a decade earlier, Eqbal emphasized that the ongoing insurgency against the United States symbolized the Vietnamese people’s continued struggle for liberation. At a time when the war was not yet prominent in American public, Eqbal also issued a stark warning: without the fear of sanctions, a foreign power in counter-guerrilla struggles may resort to genocide as a final move for “victory.”

Later, he would argue that:

It is the intellectual’s responsibility to affirm what is good and just and to resist what is bad and unjust. We have often done the reverse, but I am defining responsibility in that simple sense… The argument envisions a permanent symbiosis of opposites, of choices, between affirmation and resistance, distance and immersion in intellectual life. When intellectuals lose sight of these choices, of this symbiosis, intellect begins to stagnate. Creativity suffers, and people lose hope and faith in the future.

Eqbal, however, was never stagnant in his pursuit of justice. Throughout his 40 years in the United States, he maintained a critical distance from state power and ideologies, consistently upholding his commitments and analyses and extending his focus well beyond Vietnam.

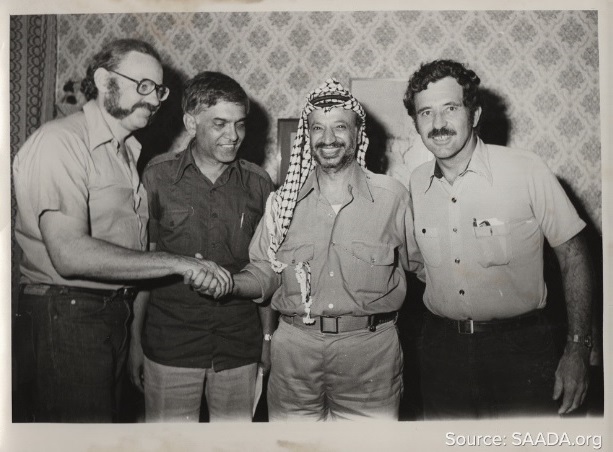

Following the Six-Day War in June 1967, Eqbal became deeply involved with the Arab American movement, especially with the rise of the Arab American University Graduates group (or the AAUG). This organization was founded by prominent Arab American intellectuals like Ibrahim Abu-Lughod, Elaine Hagopian, Naseer Aruri, Abdeen Jabara, and Edward Said, amongst others. Their primary objectives were to advocate for the Arab cause to the American public and to strengthen connections between Arab Americans in the diaspora and Arabs in the region.

It was during this period that Eqbal first met Edward Said. In a letter to producers of BBC Music and Arts, Eqbal recalled the moment he first learned about Said, after reading “Portrait of an Arab,” an article Said published in the US-based journal The Arab World. Eqbal wrote, “At a time when Israel was routinely referred to as the ‘Zionist entity,’ Said described the Palestinian Arab as a shadow of the Jew — tormented, persecuted, and devalued.” Said’s article would lay the groundwork for his magnum opus, Orientalism, but well-before its publication Eqbal was so moved by Said’s writing that he asked his close friend Ibrahim Abu-Lughod to introduce them. That was 1968.

A friendship spanning over 30 years blossomed from this encounter. However, it was not just their shared intellectual interests that defined their relationship. As Eqbal described, it was the fact that they were both exiles: “We shared the exiles’ experience in several ways, particularly in how it induces a certain relationship of alienation and intimacy with one’s chosen environment, and constant secret negotiations between one’s colonial past and contemporary metropolitan life.” Theirs was a relationship forged out of colonial dispossession and displacement, shaping their anti-imperialist outlook amid the turbulent backdrop of the Vietnam War and the continued Israeli settler colonization of Palestine.

The 1967 War had a profound impact on Said, shaping him both politically and intellectually. While his scholarship has been extensively analyzed, less attention has been paid to his comrade, guru, and true friend, Eqbal Ahmad, to whom Said dedicated his book Culture and Imperialism. In Said’s words:

Eqbal embodied not just the politics of empire but that whole fabric of experience expressed in human life itself, rather than in economic rules and reductive formulas. What Eqbal understood about the experience of empire was the domination of empire in all its forms, but also the creativity, originality, and vision created in resistance to it.

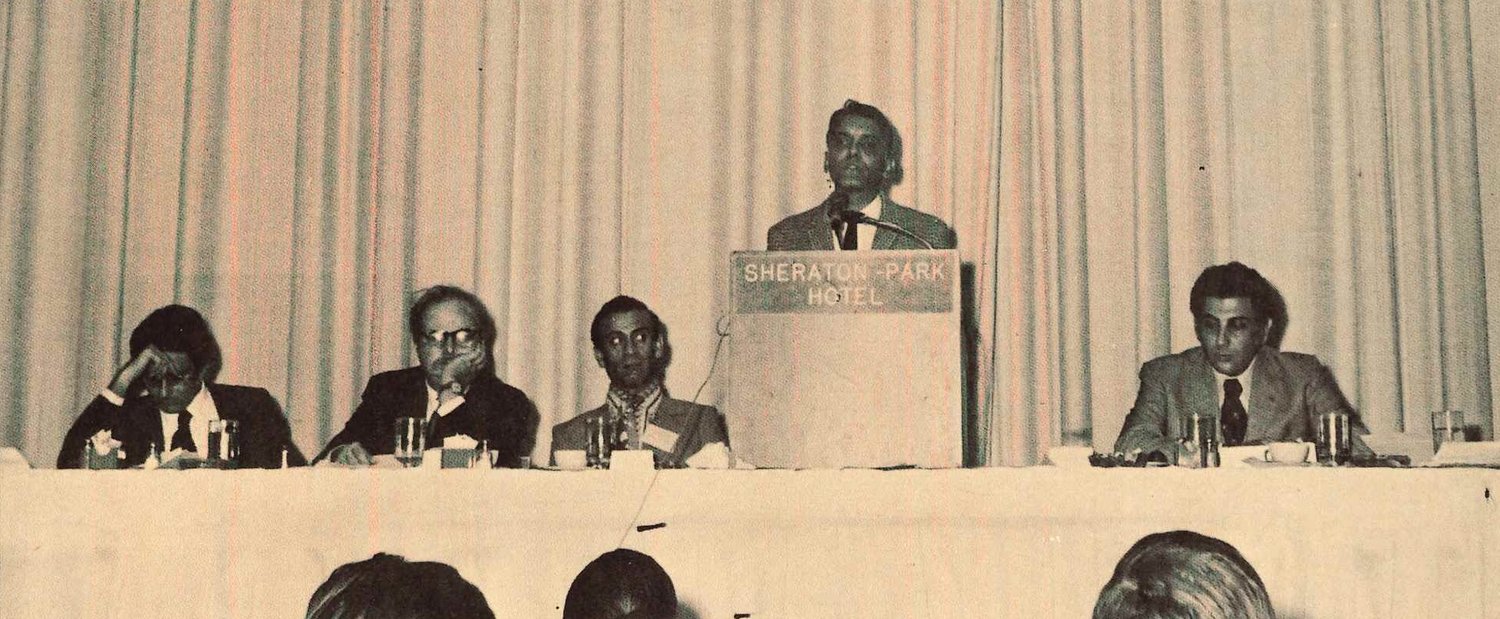

Eqbal’s ability to articulate his anti-imperialist views was vividly demonstrated on the eve of the 1970s when he addressed the AAUG audience in place of the renowned British Pakistani intellectual, Tariq Ali. Ali was unable to attend due to a visa denial by the US State Department after the burning of an American flag at an anti-war demonstration in London. In his absence, Eqbal delivered poignant statements that encapsulated both his political thinking and the creativity, originality, and vision that Said would come to admire. His remarks resonated strongly with the audience as they critiqued US military aggression in Vietnam and condemned US support for Zionism. “The reason [Tariq] Ali is not here,” he said, “is because they claimed he burnt the American flag. This is a damn lie; he did not burn the flag, he cremated it.” Eqbal’s use of the word “cremated” distilled that desire for the death of imperialism. He urged the audience to look beyond narrow nationalist perspectives and adopt a more critical view of US global power, arguing that “American imperialism is not born from Zionism” but rather “Zionism is the product of Western racism, colonialism, and imperialism — forces which are now represented by the United States of America.” For Eqbal, Vietnam and Palestine exemplified the farce behind the American ideals of freedom and democracy, ideals symbolized by the American flag. Naming its burning a cremation was a powerful rejection of a symbol increasingly seen as representing oppression rather than liberation. His speech and subsequent involvement would add to the Third World revolutionary fervor among the AAUG and its members.

Historians Pamela Pennock and Suraya Khan have analyzed how the AAUG strategically integrated Palestine into the broader Third World context, enabling Arab Americans to address the Palestinian issue within the larger framework of decolonization around the globe. The approach not only garnered widespread support from the anti-imperialist Left but was further bolstered by the involvement of prominent Third World figures like Eqbal and even Stokely Carmichael.

Throughout the 1970s, Eqbal’s anticolonial and antiwar politics would deeply shape his engagement with the AAUG, on Palestine, and other related movements. Despite his involvement in the Harrisburg court case in 1971, where he and six others were charged with conspiring to kidnap Secretary of State Henry Kissinger and destroy government property, Eqbal continued to write and engage in interviews. Although the trial ended in a hung jury, the AAUG, guided by leaders like Ibrahim Abu-Lughod, came to his defense and organized a campaign to support his legal fund.

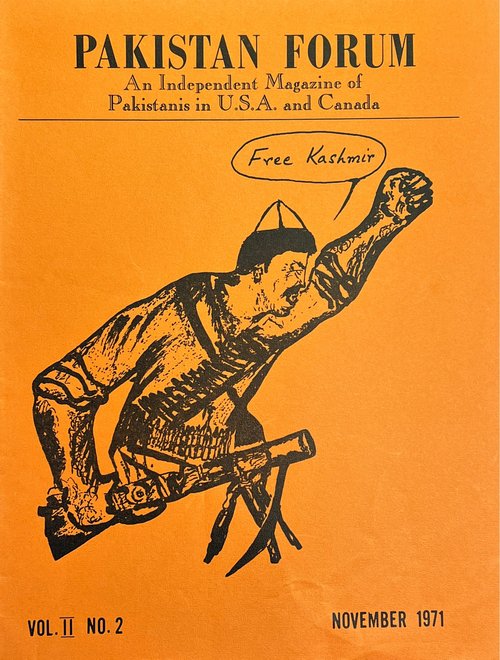

During this period, Eqbal, along with his colleagues Aijaz Ahmad and Feroz Ahmad, and his brother Saghir Ahmad (before Saghir’s unexpected passing), became involved with Pakistan Forum, a leftist journal. The journal sought to push Pakistanis, both domestically and abroad, further to the left following the overthrow of military dictator Ayub Khan by a popular movement of students and workers.

Amid rising counterinsurgency efforts in the 1970s, Eqbal authored several essays and interviews for the journal that highlighted his global political thought, providing a framework for considering the relations across interconnected geographies of empire. In “Israel and USA: Towards a New Pact,” published at the beginning of 1971 before war would erupt in South Asia and before the conspiracy charges, Eqbal examined the deepening alliance between Israel and the United States. He argued that the White House was positioning Israel as a military force in the Mediterranean intended to counter Soviet influence over Arab states, particularly in light of Western Europe’s waning power in the region, as well as to oppose the growing Palestinian liberation movements following the 1967 war. However, he would suggest that the “speed and extent of the failure” of this alliance would depend highly on the revolutionary movements in the region.

According to Eqbal, the success of any revolutionary movement was highly contingent on enhancing the unpopularity and internal contradictions of the existing coercive regime and “as the Vietnamese have amply demonstrated, the most successful revolutionary guerrillas do not readily cut the roads. They get into the bus.” In other words, the most effective guerrilla does not directly destroy infrastructure but integrates into everyday life and activities, blending in with the civilian population — a tactic that allows them to build their movement and gain popular support. By “getting into the bus,” guerrillas become embedded within the societal fabric, making them more elusive and capable of striking quickly when necessary – a strategy political theorist Geo Maher might describe as an anticolonial eruption.

In 1971, Eqbal was interviewed by Al-Hurriya, a newspaper associated with the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine, an interview that would also appear in an issue of Pakistan Forum. While many of the articles in the 1971 publication of Pakistan Forum would address South Asian national liberation struggles in Kashmir and Bangladesh, the inclusion of Eqbal’s interview about Palestine could perhaps be seen as out of place. However, in a 1972 editorial, Eqbal clarified that the journal, while dedicated to being an “independent, critical, and combative” platform against the reinforcement of military and bureaucratic power in Pakistan, also sought to challenge global imperial power. Addressing a predominantly global Pakistani audience, his writings and interviews, along with his solidarity with national liberation and self-determination movements in Palestine, Bangladesh, Kashmir, and Vietnam, were grounded in the principle that these struggles were interconnected. He aimed to highlight how the Mediterranean and Indian Ocean regions were increasingly becoming a “junior partner in the US-controlled, anti-Arab, anti-Communist, pro-Israeli constellation of imperial power.” He argued that hope for revolutionary change did not rest with the postcolonial state, which he viewed as increasingly militarized and authoritarian. Instead, he placed his faith in an intelligentsia not on the state’s payroll and capable of offering sharp analyses and charting a way forward, alongside the common people. He believed that the radical political culture fostered by revolutionary social movements would be unstoppable if we all just got on that bus together.

“When carried out with strategy, revolutionary violence and sabotage, [Eqbal] believed, can ‘free the people from the constraints of coercive authority.’”

In the same interview, Eqbal discussed the challenging questions and attitudes surrounding the legitimacy of using terror in revolutionary movements. He noted that “terrorism,” “political assassination,” and “armed struggle” must be understood in their historical and political contexts. He emphasized, as he consistently did throughout his life, that the primary goal for any revolutionary movement is to delegitimize and morally isolate the existing regime — an important and exceptionally difficult political task. While Eqbal did not romanticize revolutionary violence, he acknowledged its importance in movement-building and its potential to ensure the survival of militants, provided it is executed strategically and justly, rather than indiscriminately. When carried out with strategy, revolutionary violence and sabotage, he believed, can “free the people from the constraints of coercive authority.”The ongoing genocide of Palestinians in Gaza has sparked renewed debates and divisions on the left over the role of armed struggle. The prospects for building a robust and unified global anti-imperialist movement seem to be further constrained by the rise of the counterterrorist state during the long war on terror. Increasingly, movements — particularly those led by Palestinians and Muslims — have become entangled in the narratives and practices of counterterrorism, which unjustly depict all resistance to colonialism, occupation, apartheid, and genocide as inherently illegitimate and undignified.

When the Western left and intelligentsia dismiss the anticolonial aims of liberation movements like Hamas and Islamic Jihad, they not only undermine Palestinians’ struggle for self-determination but also reinforce the legitimacy of the counterterrorist state. By (sometimes unwittingly) adopting the state’s counterterrorism logic, the left faces a growing challenge: how can it oppose the resurgence of global authoritarian nationalisms while continuing to dismiss those at the forefront of resistance against colonialism, occupation, apartheid, and genocide? As the “war on terror” increasingly morphs into a “war on the left,” with the counterterrorist state expanding its reach to target more and more movements, it is crucial for the Western left to align with those on the frontlines. By doing so, we can forge new solidarities among Palestinians, Arabs, South Asians, African Americans, and Muslims — moving beyond the secular-liberal-Orientalist framework that continues to cast these groups through an imperial lens of suspicion.

“As Palestinian poet Mosab Abu Toha recently articulated, Palestinians need us not simply to wake up, but to rise and confront the monsters of our time. ”