Disclaimer: The Eqbal Ahmad Centre for Public Education (EACPE) encourages critical and independent thinking and believes in a free expression of one’s opinion. However, the views expressed in contributed articles are solely those of their respective authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the EACPE.

Rule of the law and the equality before the law entail an important principle of equal status of citizen in society. The social contract theory envisions the intermingling of state and society on reciprocal basis which demands equality in both rights and obligations from both sides. The concept of citizenship is deeply linked with the modern notion of nation-state which envisages granting equal rights to all the people inhabited within its territory. The very concepts of liberty and fraternity as derived from French Revolution form the core of the equality of all people before the law. However, it is to be noted that equal rights for citizens and equality of citizens has more or less moral grounding rooted into the ethical and legal structure of the nation state—making it a legitimate entity in the eyes of public. Pakistan, once carved out from British India, carried raison de’tre of protection of rights of Muslim minority from the clutches of Hindu majority. Now minorities in Pakistan are living in constant atmosphere of fear and hate from the majority. How, over the years, the status of minorities has plummeted from protective to vulnerable section of society? How their concerns can be rectified in the context of current state of affairs? How their status as equal citizens of the state can be rejuvenated? These are but few questions which would be addressed in this article.

The state, in the past, fed mainly on the negative profiling of the ethnic as well as religious minorities in order to germinate and prolong nationalistic sentiments.

Since the foundation of the state, there is a strict bifurcation of Pakistan along majoritarian and minority lines which has been further deepened over the years—making Pakistan increasingly a minority-less state. This dismal state of affairs is not merely confined to ordinary minority groups and communities; rather the sojourn of marginalization of minority groups runs deep into the structure of the state. Amongst 69 members of First Constituent Assembly of Pakistan, 15 were from minority groups. The first Law Minister was a Hindu. The first army chief was a Christian. The shift from pluralism and peaceful co-existence to puritarianism has result into the purification of Pakistan from religious minorities. From the 16 percent of the total minority at the time of independence, now a meager 4 percent is remnant—that is also under constant assault. According to the Population Census of 1998, the overwhelming majority of Pakistan is Muslim which constitutes about 96.58 percent of total population. US Department’s International Religious Freedom Report (2012) placed Pakistan in top ten states where minorities are at high risk of extermination at the hands of majority. It is just like naming a dog and hanging it. The miniscule minority left behind in Pakistan is highly vulnerable to the majoritarian nationalistic and religious ambitions. The majority of people love to hate ‘the Other’. This shared perception of hostility for ‘the Other’ in the form of minority groups forms the backbone of mainstream national narrative as a defining variable for elaborating religio-nationalistic roots of Pakistani society. In fact, the state, in the past, fed mainly on the negative profiling of the ethnic as well as religious minorities in order to germinate and prolong nationalistic sentiments. This dominant practice of rationalization of nationalism by marginalization of minority groups has results into monochromatic practices of ideational statism in predominant policy making orbits—a reflection of shift from community based national interests to state-based national interests. Dr. Mohammad Waseem writing in Dawn noted that ‘It (the state of Pakistan) moved from a representational model of state-society relations to a mobilisational model of the national agenda.’ The constant alignment of the state with the religion of the majority casts doubts on the loyalty and patriotism of minority groups.

Despite some remedial steps like formation of Ministry of National Harmony and its subsequent conflation with Ministry for Religious Affairs, Pakistan is still marked by acrimony at domestic level towards its communities. Inter-faith dialogues and pro-peace seminars have increased some awareness about the rights and plight of minorities in Pakistan, but the scope of their activities has been very limited owing to a small coterie of liberal section engaged in this whole exercise. This section is well articulate in its opinion, but not well organized to make a significant impact at policy level. The religious section is still enmeshed in the mist of re-interpretation of religious ideals in the context of begetting good relationship with religious ‘Other.’ The culture of forces marriages and conversions in the rural Sindh has put a stigma on the face of religious practices in the meanwhile—the price of which Pakistan would pay in the form of international protests.

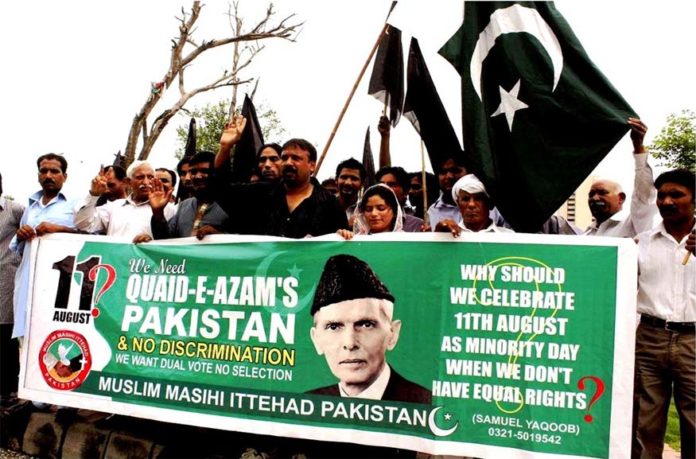

The state has to play its proactive role to rekindle the agenda of making Pakistan a pluralistic state in line with the vision of Mohammad Ali Jinnah.

In this current morass, what can be done to save what has been left behind in Pakistan? The state has to play its proactive role to rekindle the agenda of making Pakistan a pluralistic state in line with the vision of Mohammad Ali Jinnah. It can be done by eliminating all the hate messages through a robust policy of economic, academic and cultural transformation and redefinition of national interests in broader context of public good and communities’ betterment. This policy has to be predicated on the fundamental notions of public and individual rights. The modern means of communication like media have to be completely banned from spreading and hate messages against any minority groups. If Pakistan want to progress on the ideals and ideas of its founding fathers, it has to recognize that internal stability and stable relationship amongst different religious groups forms the basis of innovation and creativity to compete in globalized world.

Contributed by Hammad Raza