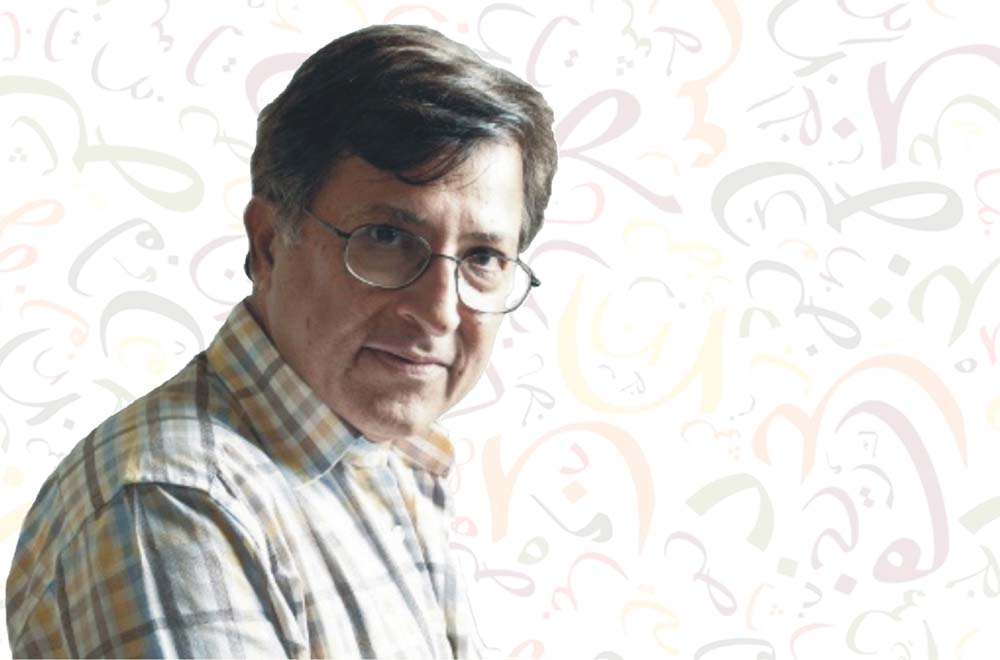

This conversation with Professor Pervez Hoodbhoy is presented as a three part series. Part 1 covers Pakistan’s education system. Part 2 discusses Pakistan’s language conundrum. Part 3 includes a conversation regarding South Asian politics and culture.

~

Pakistan’s Language Conundrum

Hassan Mirza (HM): The English language continues to dominate South Asia in many spheres of life, and its authority is almost unchallenged by many of the local languages. Will Urdu (also Hindi in India) fade away in a century’s time and be replaced by English completely in Pakistan (and in India)? What is the future of Urdu and Hindi?

Pervez Hoodbhoy (PH): Urdu is certainly not fading away in Pakistan. That’s because the number of people who can properly speak/write English is rapidly decreasing. So a hundred years later it’ll be Urdu by default, but I think it will be some very low quality “Urdish” – an unseemly mixture of Urdu and English written in the Urdu script. Of course, sizeable numbers – maybe five to 10% of the population – will find English indispensable and have it as their primary language.

HM: You said that almost no one can speak/write English anymore, but how is this possible in this day and age where the only language of globalisation, the internet, and business is English and it has an official status in South Asia and prestige associated with it. Surely more and more people must be speaking and writing English now?

PH: Of something like one hundred private TV channels not one is in English. Most university teachers can’t teach in English although they are supposed to. Two English language TV channels (Dawn and Express) had to close down. There wasn’t enough viewership and hence advertising revenue. India is different from Pakistan now although the beginnings were not so different. English is still widely spoken there.

HM: Do you think that focusing more on Urdu will make Pakistanis more narrow-minded and less willing to learn modern knowledge? The Urdu press and literature is dominated by overtly religious people.

PH: Yes, Urdu is steeped in a religious idiom. Of course, there is Ghalib, Faiz, Josh, etc. But they represent a tiny subset. If you look at books published these days in Urdu, progressive thought is quite marginal and readers are few. I know because for 25 years I’ve been running Mashal Books which publishes modern thought in Urdu. We have a hand to mouth existence and never know when we might have to shut down.

HM: Can the script of Urdu and Hindi be changed, from Persian-Arabic and Devanagari respectively, to the Roman script? Will that help in reviving the language or is it too late by now to do so?

PH: Ayub Khan tried and failed because the backlash was fierce. I once thought that the computer would force Romanisation but it’s now fairly common to see people typing Urdu on their smart phones. A google search using Urdu script is still not around but it’s only a matter of time before that technical hurdle is overcome. This means there’ll be even less incentive to learn English.

HM: There are more than 900 million people who can speak Urdu and/or Hindi, collectively making it the third biggest language after English and Mandarin. Can India and Pakistan work together to promote this language? It is basically the same language with two standard registers.

PH: Impossible, at least in the foreseeable future. The notion that Urdu equals Muslim and Hindi equals Hindu has never gone away. Both countries are ‘purifying’ their languages, with Hindi becoming more Sanskritised and Urdu becoming more Arabic/Persian. But it’s really the influx of English words – often unnecessarily – that’s taking away from the classical beauty of both languages.

HM: Should the government stop patronising the spread of regional languages and focus only on Urdu for the sake of more social cohesion?

PH: The government doesn’t patronise these languages and looks upon them with suspicion and disdain. I think social cohesion will increase if peoples from Pakistan’s diverse regions feel that their language is respected. Local languages are associated with cultures that need preservation, protection, and propagation. Respect for local languages makes for happier societies; looking at strict functionality is not a good thing. A monoculture does not give sufficient space to people to express themselves.

HM: English and Urdu-Hindi already dominates the northern Indian Subcontinent. So what’s the point of learning and preserving some regional languages?

PH: In 30-50 years from now, 99% of all serious intellectual work will certainly be in English, not in Urdu-Hindi. But local languages will stay valuable. They are key carriers of traditions that enrich human existence. Successful societies manage to strike a happy balance between modernity and cultural traditions. Pakistan should have Urdu, but also encourage the teaching of languages from every region.

HM: The anglicised Pakistani elites often have a very derogatory attitude towards Urdu speakers. Any comments?

PH: That was certainly true for my generation. I’m from Karachi Grammar School (KGS) which was – and is – a super-elite school. And so I know very well what you’re talking about. I can’t stand my former classmates anymore because of their disdain for those they see of lower social status. Today I see Aitchison kids too and they’re no different from what we were. But in today’s Pakistan even rich kids – exceptions excluded – can’t speak English well. Although they do try certain affectations and accents, eventually they break out into Urdu. So there’s an overall degeneration in the quality of spoken and written languages. However, the most unenlightened ones in Pakistan are the Urdu medium types who have been to madrassas. Let’s not make language the touchstone of enlightenment.

Read part 1 of the interview here. and part 3 here.

Hassan Mirza

The writer is working as an applied scientist in Germany and specialises in Computer Simulations, Applied Artificial Intelligence, and Energy Modelling. In his free time he reads extensively in multiple languages (Urdu, English and German) and is interested in writing about scientific and socio-economic issues.

The writer is working as an applied scientist in Germany and specialises in Computer Simulations, Applied Artificial Intelligence, and Energy Modelling. In his free time he reads extensively in multiple languages (Urdu, English and German) and is interested in writing about scientific and socio-economic issues.

The writer is working as an applied scientist in Germany and specialises in Computer Simulations, Applied Artificial Intelligence, and Energy Modelling. In his free time he reads extensively in multiple languages (Urdu, English and German) and is interested in writing about scientific and socio-economic issues.

The writer is working as an applied scientist in Germany and specialises in Computer Simulations, Applied Artificial Intelligence, and Energy Modelling. In his free time he reads extensively in multiple languages (Urdu, English and German) and is interested in writing about scientific and socio-economic issues.

With the advent of translation engines, language is not a barrier for high quality education. India and Pakistan should quickly develop digital tools for all our local languages.