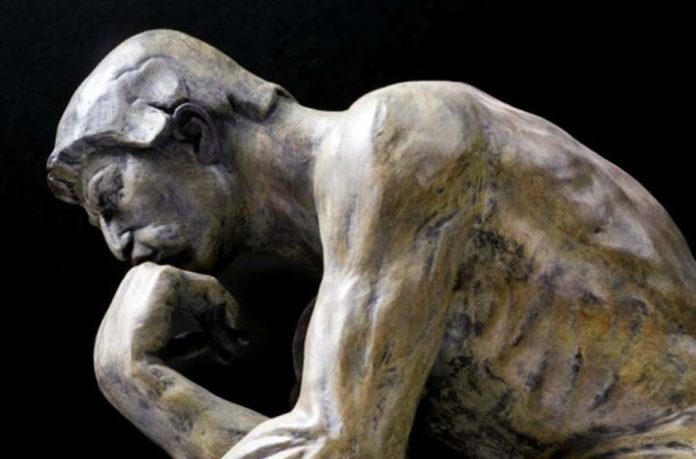

‘I WONDER’. These two words have incalculable power. It’s because of this innocuous phrase that humans stand at the top of the evolutionary ladder. Whereas animals look only for basic survival, you and I reflect, seek cause and comprehension, and speculate. Then, from wonder’s bosom springs expansive thinking. You theorise, explore depths, and perhaps have a Eureka moment. Without wonder there cannot be science or art.

Wonder lives inside children — ours too. Last week, it was a treat for me to spend an evening speaking at the Buraq Space Camp in Islamabad to 14-15 year-olds about recent scientific discoveries. Bombarded with questions about the Big Bang, atoms, and biological evolution, I had to retreat once my throat packed up. But it gladdened my day and I left reassured that wonder and curiosity are still alive in Pakistan. This, in spite of the fact that all were ‘O’-level children from elite private schools and that, sadly, not one came from a school that uses the official, government-prescribed, curriculum.

Bright, curious kids exist everywhere but here, among 200-plus million people, they are getting rather hard to find. Forget students, just look at teachers — those in our ordinary schools, colleges, and universities. Most are brain-dead duffers. I suggest you eavesdrop someday on their daily tea sessions. You will never hear them talking about the Pluto fly-by, the recent discovery of a three-million-year-old ape-human, or anything substantive. Instead there’ll be gossip, titbits about celebrities, or the prices of meats and vegetables.

Bright, curious kids exist everywhere but here they are getting rather hard to find.

Why so little curiosity about the larger world? Why no urge to know what lies in or beyond it? Some 120-plus TV channels have political talk shows, religious programmes, fashion, and cooking. But not one produces programmes on discovery, science, or world history.

This reduced collective appetite for wonder has two reasons. One is straightforwardly identifiable: the preponderance of closed, pre-modern thinking in society. The other, curiously enough, is a modern disease that is sure to get worse as technology improves. Each shapes attitudes in a distinctly different way.

Lethal to wonder and curiosity is Pakistan’s education system. Like every traditional system of thought, it is built around pre-modern and pre-scientific values. These allow for inquiry, but only a little. At its core is the belief that knowledge pre-exists in texts, whether holy or secular. The teacher’s job is to convey unchallengeable facts to the student, and the student’s job is to learn them. Religious knowledge and secular knowledge are taught in practically identical ways. Read, reproduce, and reap the reward — a good student is a good hafiz.

Wonder is tightly constrained in every strictly traditional system. Yes, man is allowed to discover. But he cannot be seen as inventing new knowledge lest he also seem a creator. Thus the path to true knowledge is to learn Hebrew, Latin, Sanskrit, or Arabic and become a good exegete. But this tight box sometimes doesn’t suit independent inquiry very well.

Example: suppose you wondered why Earth has water. The explanation from a rabbi, priest, or aalim would be teleological — water had to be there because the universe’s designer wanted life to exist. This surely damps curiosity although the persistent mind can still ask: why don’t other planets have water? Did water come from the steady bombardment of frozen meteorites or was it always there? Most importantly, how can we know what is true?

The conflict between modern and traditional values of education is creating hybrids that bewilder students. They’ve been told that acquiring knowledge is their holy duty. This is certainly true for religious knowledge. But what about other things?

For example, students play with batteries, wires, and magnets because it’s fun and it teaches them about electricity. They mix two colourless liquids to produce something brilliantly blue-green and so learn chemical facts. They learn Java because it makes smartphones or computers function in a certain way. What’s thoroughly confusing is that no holy edict demands this.

Paradoxically, at another level, a post-industrial age product — the Internet — is also creating a wonder deficit. True, instant access to the world of ideas and information helps titillate the imagination, and is directly responsible for the explosive growth of new knowledge. But Google and smartphones are turning many smart kids into dullards and dimwits.

The problem is that search engines have made things too easy. Before you’ve even finished typing in a question, it’s likely that the answer will be on your screen. Without your smartphone or I-Pad you might have engaged in a stimulating discussion with your friend, racked your brains, and reflected upon possibilities. Through spirited debate you could have tried to convince him he was wrong and you were right. Instead, one keystroke ends everything. Instant gratification stills your neurons even before they can fire.

More dangerously, oceans of disinformation are available to undisciplined and badly educated minds. Hence wacky ideas like Osama bin Laden having died a decade ago, 9/11 being a Jewish conspiracy, or that Mr Pathan’s famous ‘water car’ was killed by American pressure, thrive among today’s youth. Many absorb falsified facts about splitting of the moon (Photoshop be blessed!) or that the Apollo landing is a fakery.

Although wild conspiracy theories grow everywhere, they grow faster where education is loaded with pre-modern ideas and values. Minds formed in such social environments benefit little from instantaneous access to information. They stay incurious and undiscerning, concerned largely with the mundane.

The Internet was supposed to feed wonder. Yes, it certainly can — but only if good, modern education instals the mental structures needed for sifting and critically examining information. As with many technologies, we have here a double-edged sword. To use the right edge is important.

Correct use must first recognise that facts are just ingredients, not knowledge itself. Knowledge enhances wonder, it doesn’t kill it. In a well-disciplined mind with robust reasoning skills, wonder inspires science, art and poetry. These, in turn, feed the appetite that wonder excites in us and helps us escape the drab world of appearances, generating epicycles of boundless creativity and enduring inquiry.