Pakistan’s powerful political class has used all possible means, extreme violence included, to enhance its personal wealth and interests. Theft of public lands must therefore count among relatively minor sins. Case in point: the brazen takeover of Quaid-i-Azam University’s land by a powerful politician. In another country, this would have led to an uproar — but here, apart from a few noises, there has been nothing.

A mere land grab might be unworthy of mention except that, as the crow flies, QAU is barely two miles from the presidency, Prime Minister’s Secretariat, and Supreme Court. And yet those sitting inside the very heart of Pakistan’s establishment — whether indifferent or complicit — have so far not sought to reverse a wrong that imperils the future of the country’s premier public university.

Even a short walk inside the campus tells of something terribly wrong. An Arab-style palace stands with multiple SUVs parked in the driveway. Barricades, gun-toting guards, and menacing dogs dissuade the curious passerby from coming too close. Two years ago, after much hesitation, QAU’s estate office posted warning signs against encroachments, but they were torn down within hours. The exercise was not repeated — QAU’s security guards would have been no match for a heavily armed militia.

Undoing the theft of QAU’s land will be a strong test of PTI’s stated resolve to fight corruption.

The palace’s owner proudly identifies himself as former chairman of the Pakistan Senate and a member of the PPP. For a few short days during 2013, he had also been the acting president of Pakistan. Soon upon achieving that distinction, QAU authorities were summoned to his palace. Thereafter, a hitherto unnamed road running across the campus suddenly acquired a signboard — Nayyar Bukhari Road. But this was just the beginning. Dozens of smaller houses have since sprouted. Said to be built by the palace owner’s relatives, they have been sold onwards. Space for the university is steadily shrinking.

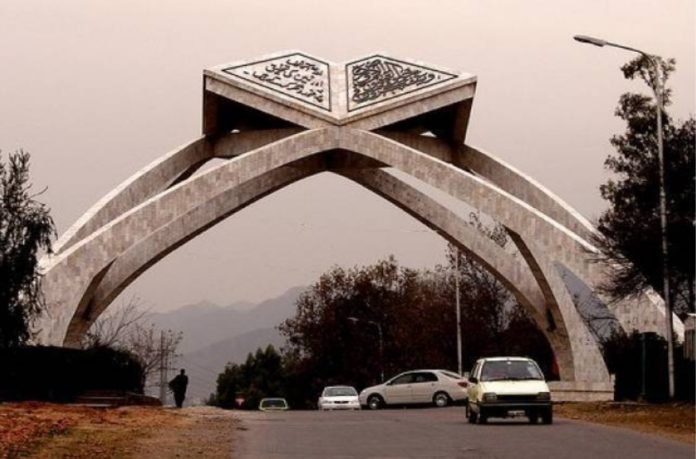

The story of QAU’s land goes like this. Back in 1966-1967, Islamabad University (later renamed Quaid-i-Azam University) was located in Rawalpindi. With the new sister city of Islamabad coming up fast, a decision was made to relocate the university at the foot of the Margalla Hills. Thereupon, 1,709 acres were allocated by the Capital Development Authority. After due official formalities, the requisite sum was paid from the university’s budget and a receipt obtained. On Jan 26, 1967, CDA issued an official map establishing the university’s boundaries.

Fast forward to 1996: QAU’s choice land attracted the attention of many, including prime minister Benazir Bhutto. Although this land rightfully belonged to future generations of Pakistanis, she sought to reward her cronies in parliament by offering them plots on campus. Available at a fraction of the then market price, the land’s value was expected to further multiply with time. Potential resistance from QAU teachers and employees was short-circuited by offering them smaller plots — also vastly underpriced.

Parliamentarians and university teachers rushed to pay their first instalments and solemnise the transaction. As mountains of cash beckoned, consciences flew out of the window. Also queuing up were parliamentarians from opposition parties. So lucrative was the deal that some spoke of switching party loyalties. Alarmed, PML-N chief Nawaz Sharif forbade his party’s members to participate in the land grab. His admonition fell upon deaf ears.

As it turned out, that deal collapsed. Public interest litigation, with pro bono help from eminent lawyer Abid Hasan Manto, ultimately helped a few QAU teachers foil Bhutto’s plan. The court ruled that QAU’s land was a public trust not to be converted to private property. This victory, and the fortuitous dismissal of Bhutto’s government by president Farooq Leghari, put an end to the land grab. Or so it then seemed.

But 10 years later, the land grabbers returned — this time surreptitiously. Notwithstanding the detailed contour map issued by the CDA in 1967 (reconfirmed on Jan 24, 2017), the land records held by patwaris were stealthily altered to reduce QAU’s acreage by an astonishing 264 acres! The CDA, known as the muscular enforcer of Islamabad’s zoning laws, went silent even as QAU protested. Against a political heavyweight, a token protest was all that QAU’s various vice chancellors and registrars could manage.

But in 2015, a newly arrived VC chose to make a brave stand after he discovered that large chunks of campus land had been nibbled away. To his dismay, the CDA insisted on stopping construction of QAU’s boundary wall, the erection of which had become a legal necessity after the terrorist attack on the Army Public School in 2014. Unfortunately, weakened because of other difficulties, he was unable to fight back effectively. While some of the wall has been built, no portion exists anywhere close to the Bukhari Palace.

What are the chances of QAU recovering its looted land? There finally seems to be hope.

First, the PTI government looks committed to removing encroachments from public land. Scores of demolished buildings, presumably illegally constructed, are visible in different parts of Islamabad and Rawalpindi. On both sides of Kashmir Highway, for example, rubble stretches for miles. Most pleasing, at least to me, is the bulldozing of a hilltop McDonalds — an outrageously egregious encroachment.

Second, Imran Khan is furiously gunning for Asif Zardari. Now in hot water, Zardari may not have much time or energy to spend protecting those of his cronies who gorged themselves on land grabs. Most encouragingly, QAU’s new administration has mustered the courage to make a public announcement. On Dec 2, 2018, four Urdu newspapers carried a paid advertisement warning that, “encroachers must immediately vacate QAU’s land whose detailed map (as of 1967) has been confirmed by both the Survey of Pakistan and by the CDA.”

Scope still exists for U-turns and under the table deals. Moreover the beneficiaries of land grabbing have multiplied their numbers with each year, making it ever harder to vacate QAU land. Still, since the issue is back in the glare of public scrutiny, one has greater reason for optimism than before. This, like no other, shall be a litmus test of PTI’s sincerity in fighting corruption.