Disclaimer: The Eqbal Ahmad Centre for Public Education (EACPE) encourages critical and independent thinking and believes in a free expression of one’s opinion. However, the views expressed in contributed articles are solely those of their respective authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the EACPE.

Somewhere in rural Punjab, a poor peasant family was moving from one hamlet to another in search of better opportunities to earn their meagre bread. As they trudged on their dusty, arduous trek, they picked up a disused window frame with a few intact panes of coloured glass from a debris pile outside a small town. This was their only colourful possession beside a worn out hoe, a hatchet, few nondescript pots and pans, and an ugly roll of filthy bedding. A skinny goat also tagged along, nibbling occasionally at dry twigs, stray chaff, scraggy bushes and bare branches of an odd tree here and there. They had loaded this mishmash over the back of a particularly pesky beast lent to them by their new master for a speedy transfer. The donkey instinctively knew how needy the family was, therefore was extra mean.

They fixed the window in a wall of their next hut, the only decent inlet for both sunlight and fresh air. Blue, green and yellow hues of the cracked window panes intrigued their little child and helped keep him relatively calm when wearied by pangs of hunger. This window also provided them with a lone coloured view of an otherwise bleak landscape. There was nothing to cheer their lives or lessen the back-breaking burden of their strenuous living. The land they were supposed to till had been partially hit by salinity as barren patches of salt-whitened bald soil were visible here and there.

This faceless family and their goat reeked of strong earthy odours and were quite unaware of the ease with which they could offend the aristocratic senses of a well-groomed person. Neither did these peasants know any other way to present themselves when narrating their miseries nor were they capable of improving their plight.

This family is particularly familiar in a very ordinary way. You might have seen many like them lugging heavy loads or climbing dusty tracks on under-construction dam sites; crushing stones with their hammers under the blazing sun while working on rural road alignments with one hand usually covered in rags or disused rubber tube to absorb heat and missed hammer blows. They can also be seen working in the pits of newly dug canals, dressing ground ripples left over by the dredgers, and tending brick kilns with faces blackened by poverty and soot. Some of them, however, appear to have let go of their ranks and are found begging on traffic signals. Beaten to alms by professional beggars here, as well, they are left to tend a lingering inevitability of their relentless plight, no matter how much they try to break free. Their intrinsic self-reliance and built-in instincts to work hard prevent them from rummaging through the rubbish dump for discarded food.

We might have had a good idea of how our society is slowly — but irrevocably — unravelling at its very roots.

They are normally seen huddled near hardware stores to be picked up by contractors as labour for construction sites. This is an injury prone undertaking; once injured, it multiplies miseries and causes untold hardship. It also exposes them to exploitation, especially with regard to wages and non-existent work contracts.

Driven by such circumstances, these men and women can be easily pushed to the dark realms of lawlessness. Other eminent employers eyeing them with intent include gangs, militants, and foot soldier recruiters for armed wings of political, religious and ethnic parties. The rootless mass, talked at length above, provides them with a vast manpower pool. The market for unemployed females and children is limited and turns out to be traditional. Their children are disfigured and later pressed to beggary alongside ungainly females. Those who are considered attractive are pushed towards flesh trade.

By now, we might have had a good idea of how our society is slowly — but irrevocably — unravelling at its very roots. It seems natural to look for someone else to blame the ongoing malaise upon. However, this tragedy cannot set forth from one source alone. We have failed as a society. We are unconcerned and disgusted at the plight of others. As employers, we are mainly concerned with the services these poor souls render, with no thought for their future. We do not consider how they would carry on with their lives in the event of an accident that leaves them unable to render these services. Those who wish to provide them with some security in return for small savings are discouraged by their disbelief. I remember a particularly needy servant who refused to entrust me with his savings even when I offered to add an equivalent amount whenever he wished to withdraw. This is a sad reflection of hard-nosed disaffection, which has deeply seeped into our social system, making everyone fends for themselves. Then there is an incessant inadequate–or even, lack of– a provision of security net by the state, which is further amplified by our shoddy law enforcement. Both our police and legal system have notoriously failed to deliver to their needs

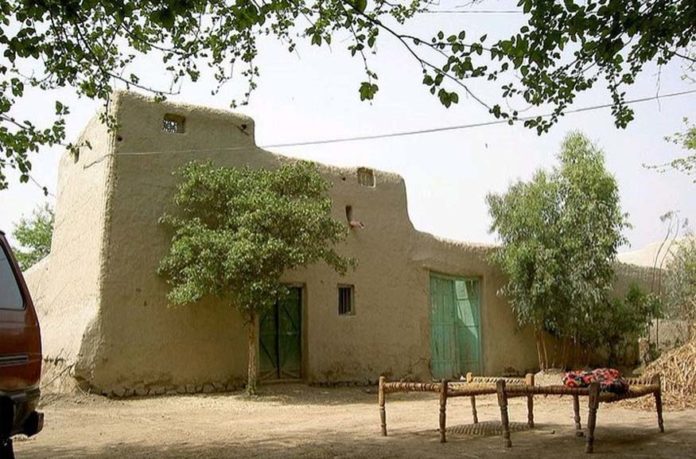

Another offshoot of this worrisome state of affairs is the ever-increasing distance between the state and the poor. The bonding between various segments of our society is coming off, which is seriously endangering the very structure of our society and disintegrating the broad base of the state. The doll house that we live in is, in fact, a mud hut with an out-of-place coloured glass window, which is situated in a land ravaged by salinity. Its walls are dissolving at the base as salt eats into the bonding mortar, turning it into dust. If we do not remedy now, our present mirage will soon evaporate to dusty whirlwinds that dance away into nothingness. What we believe exists as our plush present has already become past, if we knew any better.

Contributed by Mehboob Qadir

The writer is a retired brigadier of the Pakistan army and can be reached at clay.potter@hotmail.com