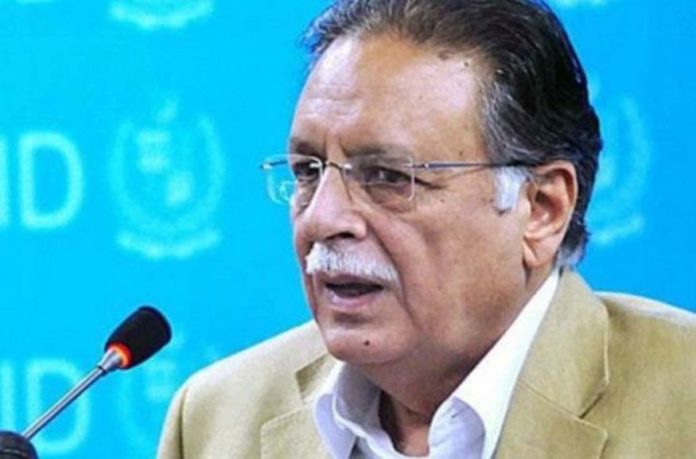

When Information Minister Pervaiz Rasheed spoke at the Karachi Arts Council on May 3, he stated the self-evident. Without explicitly naming madressahs, he said large numbers of factories mass-produce ignorance in Pakistan through propagating “murda fikr” (dead knowledge). They use loudspeakers as tools, leaving well over two million young minds ignorant, confused, and confounded. The early tradition of Muslim scholars and scientists was very vibrant and different, he said. But now blind rote learning and use of books like Maut ka manzar — marnay kay baad kya hoga? (Spectre of death — what happens after you die?) is common.

That last reference made me sit up. A best-seller in Pakistan for decades, I had bought and read my copy some 40 years ago and have since re-read it from time to time. My fascination with it, as with Dante’s Inferno, comes from the carefully detailed, blood-curdling horrors that await us in the grave and then beyond. One part of the book reports upon conversations between the inhabitants of heaven and hell. Another section specifies punishments for grave dwellers guilty of treating one of two wives unequally, disobeying one’s mother, owning more houses than necessary, or urinating incorrectly. While doubtless of grave importance, the minister’s point is easy to see.

The speech was extempore, and the minister rambled. Yet he set off a firestorm. Accused of making fun of Islamic books and Islamic teachings, clerics across Pakistan competed to denounce him. Authored by an extremist sectarian outfit, the JASWJ, banners on Islamabad’s roads appeared. They demanded that Rasheed be publicly hanged. Taken down by the police, they reappeared elsewhere. The police accosted those putting them up, but withdrew after being confronted by youthful stick-bearing students from an illegally constructed madressah in Islamabad’s posh F-6/4 area — one of the scores of other such madressahs in the city. The police chief expressed his views frankly: he was not equipped to take on religious extremists and suicide bombers.

The episode involving the information minister illustrates the present condition of state and society.

The story gets curiouser. Mufti Naeem — the powerful cleric of Karachi’s Jamia Binoria who had issued the fatwa of apostasy on Mr Rasheed — was a guest on a TV television talk show broadcast live on May 24. He reaffirmed his fatwa at the outset of the conversation. The two other guests were the Punjab law minister, Rana Sanaullah, and myself. One might have expected the law minister to insist on the rule of law, and to challenge the extrajudicial sentence passed against a colleague who sits with him in the cabinet. On the contrary, Mr Sanaullah expressed his high regard for the mufti and the mufti duly returned the compliment, expressing his delight at the minister’s recent reappointment.

The pressure on Rasheed was unbearable. Many, including the minister of defence, rushed to offer explanations and excuses for his May 3 speech. Privately they agree with him but taking a public position is another matter. Mr Rasheed too has retreated since and apologised, claiming he has been misunderstood. He was later seen at a dastarbandi (graduation) ceremony at the Al-Khalil Qur’an Complex in Rawalpindi where he distributed prizes to madressah students who had memorised the Quran. By doing so, he showed his lack of keenness in following in the footsteps of governor Salmaan Taseer.

Irrespective of the final outcome, or the personality of the individual, the Pervaiz Rasheed episode starkly illustrates the present condition of state, society, and politics in Pakistan today. One takes from it some important conclusions.

First, the urban-based clerical establishment grows bolder by the day, believing it can take on even sitting ministers or, if need be, generals. They have many tanks and nuclear weapons but didn’t Islamabad’s Lal Masjid — now grandly reconstructed — finally triumph over the Pakistan Army? Even though the clerics lost 150 students and other fighters, the then army chief sits in the dock, accused of quelling an armed insurrection against Pakistan and killing one of its ringleaders. Chastened by this episode and others, the establishment now seeks to appease the mullah. Not a single voice in government defended the information minister. Like the brave Sherry Rehman, who was also abandoned by her own party in a similar crisis situation, he was left to fend for himself.

Second, by refusing to own the remarks of its own information minister the government has signalled its retreat on a critical front — madressah reform. This part of the National Action Plan to counter terrorism involves financial audits of madressahs, revealing funding sources, curriculum expansion and revision, and monitoring of activities. Some apparent urgency was injected after Interior Minister Chaudhry Nisar’s off-the-cuff remark earlier this year that about 10pc of madressahs were extremist. Even if one-third of this is true, this suggests that there are many hundreds of such seminaries. Plans for dealing with them have apparently been shelved once again.

Third, one sees that open television access was given to clerics and other hardliners who claimed that Mr Rasheed had forfeited his right to be called a Muslim. This is clear incitement to murder since a good fraction of society believes that apostates need to be eliminated. Such ideological extremism on TV is far too common these days to deserve much comment. Still, it is remarkable that a serving minister — and that too of information and communications — was allowed to be targeted. Has Pemra also fallen in the hands of extremist sympathisers?

For a while the Peshawar massacre had interrupted the deep slumber of Pakistan’s military and civil establishment. That those who slaughtered children at the Army Public School were not agents of India, Israel, or America came as a huge shock. It turned out that the killers were religious fanatics who saw their acts as paving their path to al-jannah. But dealing with this disturbing reality requires more wisdom and courage than Pakistan’s establishment can presently muster. It is lulling itself back to sleep by tossing more bombs into Waziristan, and lazily blaming five subsequent massacres upon RAW’s hidden hand. This is infinitely easier than dealing with the enemy within. Unfortunately it cannot work.