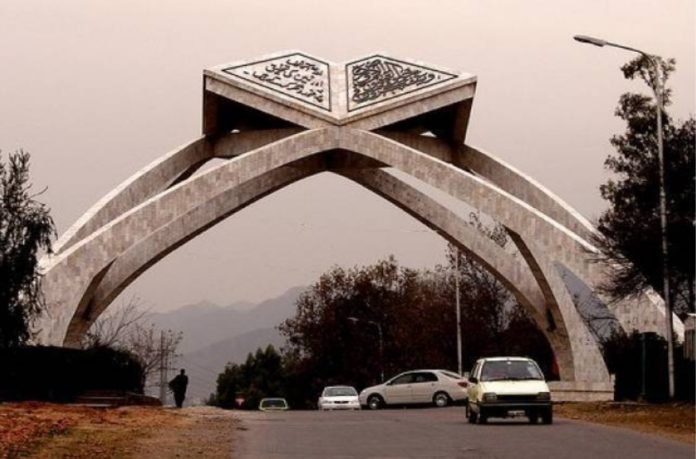

DAY 23 (Friday): Quaid-e-Azam University has finally reopened although student attendance is low and university buses are anchored off campus to avoid being damaged once again by protesters. The days ahead are uncertain. Earlier, after having briefly opened two weeks ago, students forced it shut again. Several well-meaning social activists and organisations have broadcast their support for the striking students and decried police actions leading to injuries. But such knee-jerk responses are unhelpful in understanding the present situation.

The story goes back to May when two wolf packs — one Sindhi and the other Baloch — went at each other savagely with hockey sticks and dandas, injuring dozens. Punjabi students — discernible through their accents — gleefully egged them to fight harder. The episode was recorded on their smartphones and subsequently uploaded onto Facebook pages. Sensationalist TV channels instantly picked these up and broadcast them. The police, which arrived on campus at the administration’s request, can be seen in these clips watching from a safe distance.

Subsequent to this episode various QAU student groups have created ever-growing cocktails of demands. Some are legitimate, others not. It’s all very confusing for outsiders. But here’s what the current strike is not about.

The most worrying aspect of the QAU strike is that it exposes Pakistan’s failed attempt at nation building.

First, the strike has nothing to do with any grand national issue or matter of principle. It started as a gang war between students divided by ethnicity, not ideology. The strikers are not demanding justice for Sindh or Balochistan, nor seeking to convey the sense of deprivation felt by the two Pakistani provinces. Yet, the expelled students (who are now united and chummy with each other) are willfully using their Balochistan and Sindh cards. Senators and National Assembly members from these two provinces, keen to be seen championing their constituents, have jumped into the fray. The weeks ahead will see still more of this.

Second, the strike is unrelated to that which ought to be of primary importance to students, ie improving the quality of instruction they receive at QAU. This quality is shoddy and still lower than that of past decades. Most teachers teach from age-old notes copied down from when they were students. They require rote memorisation, discourage questioning in class, and some show ethnic or sectarian bias. Many teachers are woefully incapable of explaining even simple concepts.

Third, this strike does not even touch what rightfully should be today’s burning issue on this campus — the theft of QAU land by a former PPP politician and chairman of the Senate who, together with his extended family, has made a palace on land that belongs to QAU. He has even had the audacity to construct a road to this palace. Bukhari Road runs through the campus, the declaration of a victorious land grab. This matter, after being in the news many months ago, has been allowed to subside. The CDA, whether fearful or bribed into silence, refuses to issue the clarification demanded by QAU.

The principal demand of the strikers — that students guilty of violent behaviour be forgiven — is, in my opinion, indefensible. Those identified as attackers must be punished in proportion to the degree of their wrongdoing, but after being tried through a transparent process. Only incontrovertible evidence, such as provided by videos of the episode, should be admissible.

At the same time, the present episode has given voice to those students who have long remained silent but deserve to be heard on genuine issues like the abysmal state of student hostels, overcrowding, and rudeness of teachers appointed as hostel supervisors. These teachers care little for their academic duties but hunger for power and perks.

The chief student complaint is of high tuition fees. Indeed, these have risen sharply over the last decade. This has reduced access to higher education for lower-income families, promising a future society that will be even more unequal than today’s.

The increased cost of higher education is a common issue, both nationally and globally. But it is especially serious at QAU because of much higher than average teacher salaries. Someone has to pick the tab. Who? Since the HEC has finite resources, that someone is the QAU student. The figures are horrifying: a full 70 per cent of the current QAU budget goes towards salaries for teachers and administrative staff, with the former getting the lion’s share. A professor makes between Rs350,000 to Rs400,000 monthly (perks are extra). On the other end, a naib qasid (peon) or lab assistant starts at Rs14,000!

The salary explosion owes to HEC’s misplaced belief that higher salaries would draw better teachers. There is no supportive evidence given selection mechanisms which are thoroughly corrupt, and poor ability to assess teaching quality. QAU teachers lobby hard for relaxing existing rules so that, irrespective of the state of the university’s finances, more money can somehow be siphoned into their pockets. They now want the vice chancellor sacked because infrastructural development on campus has slowed. Do these teachers think money grows on trees?

Perhaps the most worrying aspect of the QAU strike is that it exposes Pakistan’s failed attempt at nation building. As the May episode showed, ever-deepening ethnic and regional tensions need only a spark to ignite. Such tensions were far less in the 1970s. This was, I think, principally because student unions were then organised around political agendas rather than ethnic or religious ones. Banned in the 1980s by Gen Ziaul Haq, no government has dared undo the ban. Instead, as at QAU, students are pushed towards apolitical substitutes. Ethno-national councils — Punjabi, Pakhtun, Seraiki, Sindhi, and Baloch — are the only permitted organisations. This is a sure-shot recipe for further divisiveness.

The solution is not to ban ethnic councils but to conditionally restore student unions after laying down strict rules of behaviour (no violence, weapons, hate material, etc). Students urgently need to engage with issues of their times, both within and outside campuses. To become responsible citizens with mature opinions they must have political space and be exposed to diverse political philosophies. If they cannot be trusted, as some believe, then Pakistani politics will forever remain the playground of feudal lords, rich men and generals.

Nice analysis by Pervez Hoodbhoy.

I think there should be tutorial groups to bring students and teachers close and to discuss students problems.