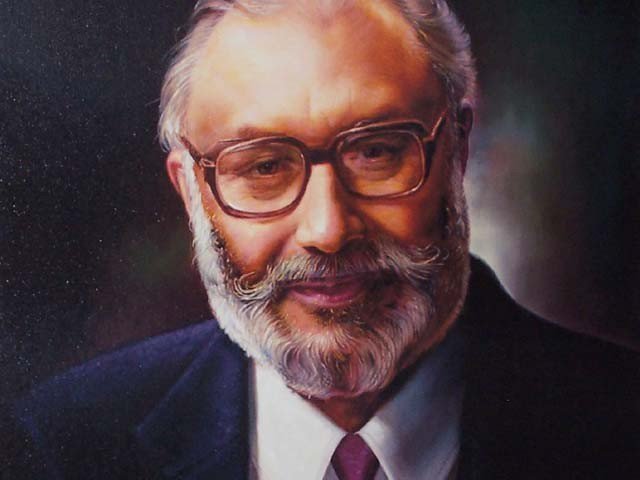

November 21, marks the death anniversary of Dr Abdus Salam – Pakistan’s only Nobel laureate and one of the legendary physicists of the 20th century. The list of his achievements and awards is so long that one wonders how an ordinary man who grew up in the outskirts of Jhang, a relatively small and less developed city in Punjab, could accomplish so much.

Yet, Jhang, the land of the Sufi saint Sultan Bahu and the burial place of Heer and Ranjha, gave us another gem, Dr Abdus Salam.

Salam truly knew what the way forward for the country was.

He had a vision for the socio-economic development of third-world countries and saw development in the progress of science. He worked tirelessly all his life towards this cause.

Abdus Salam worked as the science advisor for the Government of Pakistan and laid the infrastructure of science in the country. He also served as a founding director of SUPARCO, worked for the establishment of PAEC and contributed in PINSTECH as well. He believed in the idea of ‘Atom for Peace’ and contributed in the atomic bomb project of Pakistan.

These are just a few selected contributions out of many. Salam’s biggest dream was to establish an international research centre in Pakistan. Unfortunately, the Government of Pakistan did not show any interest in his cause and eventually Salam had to set up the International Centre for Theoretical Physics (ICTP) in Trieste, Italy, the name of which was later changed to Abdus Salam International Centre for Theoretical Physics.

Just last year, when the world of physics applauded the discovery of the ‘God-particle’, CNN’s report was enough to make us lower our heads in shame.

“Imagine a world where the merchant of death is rewarded, while a scientific visionary is disowned and forgotten. Abdus Salam, Pakistan’s only Nobel laureate, the first Muslim to win the Physics’ prize helped lay the groundwork that led to the Higgs Boson breakthrough. And yet in Pakistani schools, his name is erased from the text books…”

Although Salam worked all his life in order to serve his motherland, his countrymen failed him.

How can we even attempt to excuse ourselves from this failure?

While most countries worship their heroes, we chose to reject Abdus Salam.

Salam received the Nobel Prize in traditional Punjabi attire and quoted the verses of the Quran in his acceptance speech. However, he had already been disowned in Pakistan. On his return to Pakistan in December 1979, there was no one from the public to receive him at the airport. He was like a pariah in his own country.

He could not even give a lecture in the Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, since there were threats of violence from students belonging to Islami Jamiat-i-Talaba. This was not an isolated event and other institutes also found it difficult to invite him for the same reason. His reputation was further tarnished when the right-wing journalist stalwarts came up with their fictional stories claiming him an agent and a traitor, who had sold the country’s nuclear secrets to India.

Salam’s misery did not end here.

In 1988, he had to wait for two days in a hotel room to meet with the then Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto. However, the meeting was cancelled without any reason given.

Unfortunately, he was not even spared in death.

The epitaph on his tombstone was defaced and the word ‘Muslim’ was erased on the orders of the local magistrate. This final disgrace explains why this hero was abandoned in the first place. The theological amendment in the constitution of Pakistan does not allow members of the Ahmadiyya faith to call themselves Muslims.

Ironically for the rest of the world, Salam is still a Muslim and a hero.

While he was shunned in his own country, the world held him in high regard. The then Prime Minister of India, Indira Gandhi, invited him to India and bestowed a great gesture of respect by not only serving him tea with her own hands, but also sitting by his feet.

In Geneva, Switzerland, a road was named after him. In Beijing, the prime minister and president of China attended a dinner hosted in his honour while the South Korean president requested Salam to advise Korean scientists on how to win the Nobel Prize. Salam was also presented with dozens of honorary degrees of doctorate and awards for his hard work.

Perhaps, if Salam had been accepted and embraced in his own country, science would have enjoyed a completely different status in Pakistan. Our people may have travelled far on the road of scientific progress.

Alas, we did not.

However, it is never too late. If Pope John Paul II could apologise on behalf of the Catholic Church for the mistreatment of Galileo in the 17th century, why can’t we apologise to Salam?

We are sorry, Salam.

We are sorry for defaming you and for not understanding your worth. We are sorry for all the hatred we showed you in life and in death.

For only once a mistake is acknowledged, can one strive on the path of rectifying it.