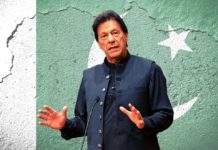

Recently, the Pakistan-initiated resolution in the UN General Assembly on the Right of National Self-Determination against Foreign Occupation was passed by a very large majority of member states supporting it. The formal enunciation of the right of national self-determination is conventionally associated with US President Woodrow Wilson’s 14 points upon which decolonisation in Europe and the Middle East took place because of the defeated powers of World War I, the Austro-Hungarian, German and Ottoman Empires, being dismembered, and new states emerging out of them.

Even at that point, it became clear that the right of self-determination was exercised by big nations while minor nations and ethnic groups were compelled to accept membership of so-called nation-states based on ethnicity and language. It was one of the principles adopted by the League of Nations.

The flawed nature of creating so-called nation-states in the name of supposedly compact nations became obvious during World War II when the Nazis invaded first Czechoslovakia and then Poland out of irredentist claims to bring all Germans under one regime.

Also noteworthy is that although Wilson’s right of self-determination was meant to become a norm of international law of Britain and France, the two main victors of World War I ensured that their transcontinental empires were not affected by it. On the other hand, VI Lenin and the Communist International wanted the right of self-determination to be extended to the Asian and African colonies of the European powers. It is worth remembering that North American and Latin American countries had gained independence from Britain, Spain and Portugal already in the 18th and 19th century.

It was only after the United Nations was founded in 1945 that the right of national self-determination was explicitly made a universal principle of international law. Both the US and USSR supported decolonisation. The first colony to attain independence was India, though it was partitioned into India and Pakistan in mid-August 1947. Next followed was Ceylon (later renamed as Sri Lanka) in 1948. It was a decision taken by the British without any major freedom struggle being launched against them.

Two possibilities exist for the formation of new states in the postcolonial era: one, that an existing state implodes and disintegrates, or that a major power intervenes to help secessionists.

In Africa, national self-determination began to be exercised from the 1950s but mainly in the 1960s. In Kenya, the Mau Mau uprising (1952-1960) was dealt with ruthlessly. The French almost everywhere dragged their feet and in Algeria a bloody civil war was fought which claimed a million lives. In the 1970s, the Portuguese colonies in the Horn of Africa were liberated after protracted civil wars in which volunteers from as far as Cuba fought on the side of the African people struggling for their liberation from colonial tutelage. The end of racist regimes in the former Rhodesia and apartheid South Africa nearly completed the process of national self-determination against foreign rule. The liberation of Palestinians from Israeli occupation is still not yet achieved.

However, decolonisation did not resolve the problem of conflicting nationalisms and national interests. The new states of Asia and Africa were themselves often multi-ethnic, multi-religious and multi-linguistic states arbitrarily left behind by colonial powers.

The question is: what happens when the right to self-determination is demanded against existing states which are members of the United Nations or who are recognised as independent sovereign states through customary law?

In the UN Charter, the right of national self-determination was presumed to be a legal right against colonial rule while the UN system is based on the right of territorial states to maintain their territorial integrity. The principle of non-interference in the internal affairs of states is another principle which upholds the right of states to maintain their territorial integrity. Therefore, there is no clear-cut right of self-determination available to disgruntled groups placed in post-colonial states. They must fight their way out of existing states if they can.

Consequently, the emergence of separatist movements in the post-World War II era against sovereign, independent states has generally met with indifference from other states: there is a systemic bias in the international system to maintain the state system and the status quo. Thus, the Kurdish bid to independence in Iraq has not found any support even when the Kurds played a leading role in the defeat of the ISIS scourge. Turkey, Iran and even Syria have Kurdish minorities and attraction for independence exists among them. The example of Syria surviving as a state despite a civil war which claimed hundreds of thousands of lives is another example of the state having precedence over separatism.

The example of Sri Lanka where the Tamil Tigers were crushed using overwhelming force by the state is another example of the state having its right to territorial integrity being upheld by the international system. The situation of Kashmir is the same. I see no possibility of the Kashmir issue being resolved against the wishes of the Indian state. The Baloch separatists also stand no chance of breaking out of Pakistan.

In Western Europe, the Catalonian bid to statehood is a major challenge and the Spanish state is not willing to let it go. The EU has no clear policy on such matters. Then we have the Scottish bid for independence, which the London government has thus far been able to frustrate through referendums in which the majority voted against leaving the UK.

However, international law is one thing and power politics is quite another. The UN system permits intervention in the international affairs of states only when reasonable grounds exist that crimes against humanity or genocide are taking place which threaten regional and world peace. On very few occasions, all the permanent members of the UN Security Council agreed on military intervention in existing states.

More crucially, a very strong systemic bias in favour of the continuation of existing states is built into the international political system of which the territorial nation-states are the foundational units. The system is seriously disturbed and destabilised when existing states disintegrate. The examples of Iraq, Libya and Syria are all before us.

Two political possibilities exist for the formation of new states in the postcolonial world: one, that an existing state implodes and disintegrates as happened in the case of the former Soviet Union and Yugoslavia or a major power intervenes to help secessionists gain independence as was seen in East Pakistan when India intervened, and Pakistan broke up. What was possible in East Pakistan separated from West Pakistan is not possible, let’s say, for the Baloch, because here the Pakistan military has logistical advantage.

About the Kashmir issue, my understanding is that the only way to resolve it is through a formula which is a win-win solution for India, Pakistan and the Kashmiris — who are a mixed lot belonging to different religions and sects, ethnic and language groups. First of all, it belongs to Chapter VI of the Security Council which means it requires the voluntary cooperation of disputing parties to resolve it; the Simla Agreement requires bilateral resolution, and in the past Pakistani administrations have shown considerable flexibility on how to resolve it. The Kasuri Plan is up to now the most practical formula for resolving it peacefully.

About the Author:

Dr. Ishtiaq Ahmed is Professor Emeritus of Political Science, Stockholm University; Visiting Professor Government College University and Honorary Senior Fellow, Institute of South Asian Studies, National University of Singapore. He can be reached at billumian@gmail.com