Download (PDF, 2.53MB)

INTRODUCTION

Science has developed with constantly-accelerating speed

40,000 years ago, our hunter-gatherer ancestors were making paintings of the animals that they hunted on the walls of the caves in which they lived. Only a blink of an eye later on the vast time-scale of evolutionary history, they were speculating about the existence of atoms. After another brief tick of the evolutionary clock, humans had invented the atomic bomb.

Genetic evolution contrasted with cultural evolution

Humans, like all animals and plants, transmit genetic information to future generations by means of the DNA and RNA macromolecules. The slow process of genetic evolution takes place through the genetic lottery, in which characteristics from one parent or the other are transmitted to the next generation in a random way. Also, random mutations of the parents DNA or RNA sometimes occur. Natural selection ensures that when these random variations are favorable, they survive, while if they are unfavorable they are discarded. Most mutations result in very early spontaneous abortions of which the mother is not even conscious.

Genetic evolution is a very slow process. Genetically we are almost identical with our hunter-gatherer ancestors of 40,000 years ago; but cultural evolution has changed our way of like beyond recognition.

Although other animals have languages, the amazing linguistic abilities of humans exceed these by many orders of magnitude. The acquisition of humans’ unique linguistic abilities seems to have occurred about 100,000-200,000 years ago. I have discussed a possible genetic mechanism for this abrupt change in another book, Languages and Classification, (2017).

The highly developed languages of our species initiated our lightning like cultural evolution, which has completely outpaced genetic evolution, and allowed humans to grow from a few million hunter-gatherers to a population of more than seven billion, to which a billion are being added every decade. Today we are so numerous that humans threaten to destroy the global environment by the sheer weight of numbers.

Acceleration of cultural evolution

Human cultural evolution began to accelerate with the invention and spread of agriculture. It began to move faster still with the invention of writing, followed by paper, ink, printing, and printing with movable type. In our own time, with transistors, microelectronics, the Internet, cell phones, Skype, and Wikipedia, cultural evolution has exploded into a constantly-morphing world-changing force.

Institutional and cultural inertia

If we look more closely at cultural evolution, we can see that it is divided into two main parts, with different rates of change. Science and technology are changing with breathtaking and constantly accelerating speed, while laws, economic practices, education, religion, ethics and political structures change more slowly. The contrast between these two rates of change has severely stressed and endangered modern human society.

For example, we still preserve the concept of the absolutely sovereign nation-state, but instantaneous global communications and economic interdependence and all-destroying modern weapons have made this concept a dangerous anachronism. As another example, we can think of our fossil-fuel-based economic system which has been made anachronistic by the urgent need to halt CO2 emissions before feedback loops take over and make human efforts to avoid catastrophic climate change futile. As a third example, we can think of social practices, such as child marriage in Africa, which lead to very high birth rates and the threat of future famine. We urgently need new ethical, educational, legal, social and political systems which will be appropriate to our new science and technology.

Tribalism and the institution of war

Compared with cultural evolution of all kinds, genetic evolution is extremely slow. Genetically and emotionally, we are almost identical to our hunter-gatherer ancestors, who lived in small tribes, competing with other tribes for territory on the grasslands of Africa. Thus it is not surprising that inherited human nature contains an element of what might be called “tribalism” – the tendency to be kind and loyal to members of one’s own group, and sometimes murderously hostile towards outsiders that are perceived as threats. The willingness of humans to sacrifice their own lives in defense of their group is explained by population genetics, which regards the group rather than the individual as the unit upon which the Darwinian forces of natural selection act.

Because human emotions contain this tendency towards tribalism, the military-industrial complexes of our modern world, and their paid political servants, find it easy to persuade citizens that they are threatened by this or that outside nation, and that obscenely large military budgets are justified.

Today the world spends 1.7 trillion dollars each year on armaments, an almost unimaginably large amount of money. It is the huge river of money that drives and perpetuates the institution of war. But today, the threat of a thermonuclear war is one of the two existential threats to human civilization and the biosphere, the other being the threat of catastrophic climate change.

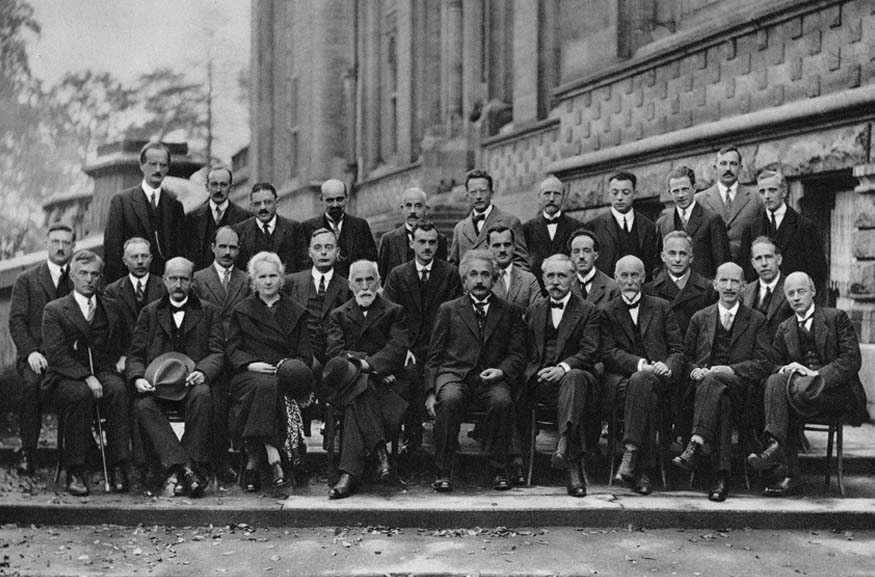

Physicists have known sin

J. Robert Oppenheimer, the leader of the Los Alamos project that constructed the first nuclear bomb, said, “In some sort of crude sense which no vulgarity, no humor, no overstatement can quite extinguish, the physicists have known sin; and this is a knowledge which they cannot lose.” He also said, “If atomic bombs are to be added as new weapons to the arsenals of a warring world, or to the arsenals of the nations preparing for war, then the time will come when mankind will curse the names of Los Alamos and Hiroshima. The people of this world must unite or they will perish.”

Science and democracy

It matters a great deal whether the results of science and technology are used constructively or whether they are used in way that harm human society or the environment. In a democracy, decisions decisions of this kind ought to be made by all of the voters. It is therefore important that a qualitative understanding of science should be part of everyone’s education.

I hope that this book will contribute to the goal of making the history of physics and its social impact available to a wide audience. I have tried to tell the story through the lives of a few of the people who have contributed importantly to the development of physics, not in an exhaustive way, but rather letting the lives of few researchers stand for many others who could equally well have been chosen. I hope that you will enjoy the book.

Read the entire book above or download it here.

We thank John Scales Avery, a renowned intellectual, EACPE board member, and theoretical chemist at the University of Copenhagen, for giving us permission to reproduce his latest book for EACPE.