Download (PDF, 3.48MB)

INTRODUCTION

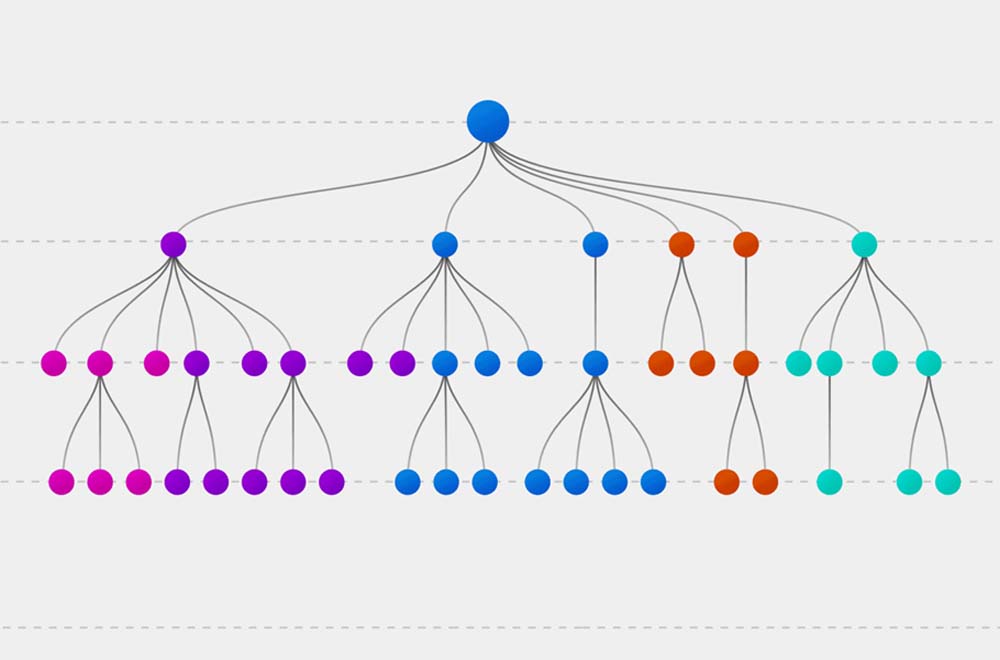

Decision trees

During each human life, a child starts with many possible destinations. He or she then makes decisions, and each decision more closely defines who the person is and what it is possible for the person to become. The choice of a vocation defines who a person is, as does the choice of a husband or wife. Often chance plays a role. The decision to take a holiday at a particular place may lead to a chance meeting with a life partner. In a human life, we can observe a treelike pattern, similar to the decision tree of a person traveling through a landscape. At each forking of the path, a decision has to be made, and that decision determines more and more closely the traveler’s ultimate destination. Analogously, in a human life, a tree-like series of decisions or external influences more and more closely define the person’s identity and destiny. Each decision is a positive step, since it helps to define a person’s character. But there is sadness too. As we step forward on the road ahead, we must renounce all other possibilities. Although we might embrace our destiny, we sometimes think with regret on the road not taken, and wonder what might have been if we had chosen other paths.

Pathfinding

The 2014 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was shared by John O’Keefe, May-Britt Moser and Edvard Moser. They received the prize for discovering the histologically observable structures in the brains of mammals which are used to remember pathways, for example the pathway through a maze. Humans also have such structures in their brains.

We can find many other examples of pathfinding in our daily lives. For example, when we send a letter or package, the address defines its path. Read backwards, it tells us first the country to which it should be sent, then the city or town, then the street, then the house or building, and finally the occupant.

We can also recognize similar pathfinding in pattern abstraction, in computer memories, and in programs of the brain.

The evolution of human languages

According to the famous linguistic scientist Noam Chomsky, the astonishing linguistic abilities of humans are qualitatively different from the far more limited abilities of other animals. Furthermore, Prof. Chomsky maintains that these abilities were not acquired gradually, over many hundreds of thousands of years, but rapidly – almost suddenly. We owe it to his high reputation as a scientist to ask how this could have happened. After all, Darwinian evolution usually proceeds very slowly, which many intermediate steps.

There are many cases where a single mutation seems to have produced duplication of a structure. For example, we sometimes see the birth of an animal with two heads, or supernumerary legs. In the light of Professor Chomsky’s observations, we ought to investigate the possibility that a single mutation caused a duplication of the pathfinding neural networks studied by Edvard Moser, May-Britt Moser, and John O’Keefe. We can then imagine that one copy of this duplicated pathfinding neural network system was modified to serve as the basis of human languages, in which the classification of words is closely analogous to the tree-like branching choice-pathways of an animal finding its way through a forest or maze.

Existentialism

According to existentialist philosophy, a person’s identity is gradually developed during the course of the person’s life, by a series of events and decisions. These events or decisions form tree-like patterns (decision trees) similar to the classification trees which Linnaeus used to define relationships between living organisms. or the grammatical classification trees in languages. We see this reflected in Jean-Paul Sartre’s famous maxim, “Existence is prior to essence”.

Positional number systems

In the decimal system, we start by asking: How many times does the number contain 100 = 1? Then we ask: How many times does the number contain 101 = 10? The next step is to ask: How many times does the number contain 102 = 100, and so on. Continuing in this way, we can obtain a decimal representation of any non-negative integer, no matter how large it is. We can recognize here a decision tree of the same kind that Linnaeus used to classify living organisms.

Had we been using a base-2 (binary) representation, the decision tree would have been as follows: We would first have asked: How many times does the number contain 20 = 1?; then How many times does it contain 21 = 2?; then How many times does it contain 22 = 4?, and so on. For example the number which is written as 65 in the decimal system becomes 100001 is the binary system. It contains 1 × 26, 1 × 100 , and 0 times all other powers of 2. The number written as 66 in the decimal system becomes 100010 in the binary system, while 67 becomes 100011, and 68 is represented by 100100.

The history of computers

If civilization survives, historians in the distant future will undoubtedly regard the invention of computers as one of the most important steps in human cultural evolution – as important as the invention of writing or the invention of printing. The possibilities of artificial intelligence have barely begun to be explored, but already the impact of computers on society is enormous.

The Internet has changed our lives completely. It is interesting to notice that the Internet is based on a package address system, and hence on decision trees. In fact, decision trees play an important role in many aspects of computing, for example the organization of computer memories.

The mechanism of cell differentiation

An embryonic stem cell is like a child at birth. The child’s destiny is not yet determined. All possibilities are open. As the child grows to be an adolescent and later an adult, his or her identity becomes gradually more and more closely defined. Choices and events begin to restrict the range of possibilities, and the person’s identity becomes more and more clear. In a closely analogous way, in the growing embryo, the cell’s identity becomes progressively more and more closely defined. In both the case of the person and that of the cell, we can recognize the operation of decision trees, like those of Linnaeus, or those of grammatical classification in languages.

Can the mechanism of cell differentiation be understood in terms of molecular biology? The final chapter of this book points to some answers.

Read the entire book above or download it here.

We thank John Scales Avery, a renowned intellectual, EACPE board member, and theoretical chemist at the University of Copenhagen, for giving us permission to reproduce his latest book for EACPE.